Buenos Aires is a huge Pandora's Box that always surprises us; for example, this time it does so with the striking collection of photographs taken by international photojournalists of one of the great figures in European history in the decades from 1920 to 1950.

When time passes the memories of the events fray, they fade and only the great moments remain. Significant names from the 20th century are preserved in memory, ranging from Lenin to Hitler, from Kennedy to Mussolini, from Albert Schweitzer to Mother Teresa, from Einstein to Oppenheimer or Von Braun, but their second lines become distant family memories or themes. of specialists, historians or curious people of the past.

If we ask who was the foreign minister of Lenin and Stalin, two no lesser leaders in history, it is difficult for anyone to know. It is impossible for us to remember who managed to delay the Stalin-Hitler pact, who restored relations between the United States and the Soviet Union, or who made it possible for Russia to survive in its early years in the face of a violent Europe. Another question that places us at a key moment in the history of the twentieth century also makes us see how difficult it is to find its answer: Who managed to convince Roosevelt to supply arms to Moscow to defeat Germany, while avoiding a war? war between them, turning it from Hot to Cold? There was a man who knew how to handle all of this with tact and intelligence, earning the respect of his own and strangers, Máksim Litvínov, who was part of the birth of the Soviet Union in 1917 until he was overtaken by the events of the World War in 1939.

His task was enormous. It is difficult to imagine the handling of the diplomatic relations of the first communist country in the world, which he helped to create from a young age, a gigantic country that emerged in the middle of a world war, and avoiding its participation in it, in addition to preventing it from being invaded. But his confrontation with the tough sectors of the Politburo in Moscow, being Jewish, coming from a high social class, speaking several languages fluently, having lived abroad and knowing the world outside Russia well, was too much. After making the USSR survive, he lost his privileges and even his dacha (the rural palace part of the luxuries that the Russian political class has) and went to sleep with a gun under his pillow to commit suicide if the KGB tried to kidnap him to deport him to a concentration camp in Siberia. He was the type of diplomat who was clear about the objectives for his country, and he knew how to do it. But in the Story, he sometimes ends up gaining brute force.

Litvínov (1876-1951) was called Meir Henoch Mojszewicz Wallach-Finkelstein and was part of a traditional Jewish banking family from Białystok (now Poland). At age 22 he joined the Social Democratic Labor Party where he adopted the name by which he would be known. He made a career of political activism and went into exile in Switzerland as a young man. From 1903 he was a member of the Communist Party as a Bolshevik and two years later he returned to Russia to edit the party's first official journal. But after a year he had to go into exile in London. He was there when the 1917 Revolution took place and Lenin considered him the representative of his government, although no one yet recognized the new country. He was again deported to Moscow where in 1918 he published a founding book: The Bolshevik Revolution: Its Rise and Meaning, which, being written in English, helped to make events in Russia more understandable. Litvínov became an ambassador traveling around Europe and at the end of the First War he was the speaking face of that world that had emerged while others were killing each other in the trenches.

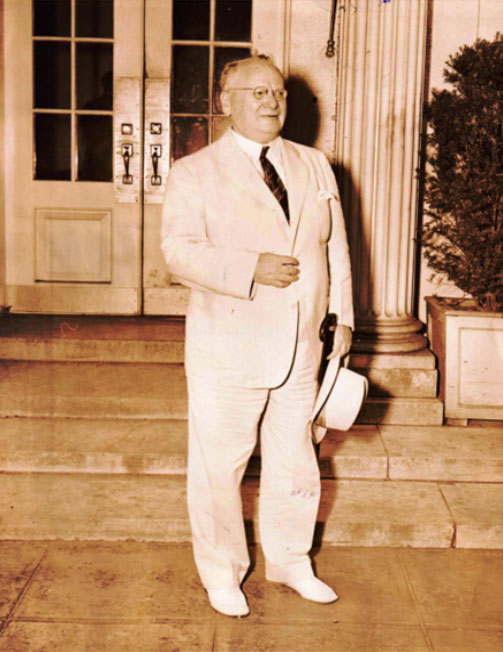

With a pleasant personal image, fluent in English and five other languages, wearing impeccable suits and upper class manners, he knew how to handle himself in the circles of high international diplomacy. And except with his boss in the Ministry, he did not have major conflicts, unlike most of the initiators of the Revolution who were assassinated or deported to the camps. His position was one of strong presence abroad, of participating in all events and meetings, and of a very low profile inside to safeguard himself from purges within the Party. One of his first achievements was to prevent the Russo-Polish war in 1920. Later he obtained official recognition from London and Paris and for this reason he was appointed Deputy Commissioner for Foreign Affairs, managing to suspend the economic blockade imposed by Great Britain; they were missions that no one could imitate. Stalin, in 1930 appointed him Commissar (Minister) although he already had powerful internal enemies, whom he faced with international achievements. He never opposed partisan purges and was an advocate of land collectivization and forced industrialization, even though it meant almost ten million deaths, most of them in the Ukraine; We don't know if that was the price for survival, or if he agreed with those internal policies that he had no chance of influencing. What mattered to him was avoiding the isolation of the country from him, so that what was later called the Iron Curtain would not rise, as a result of the terrible policies that followed.

The problems that led to the end of his career were complex, but with only one source: Germany and Hitler. For a good part of the Communist Party, its growth was a guarantee that a new power bloc would be formed in Europe, which is why they supported it; others did so because National-Socialism (Nazism) had its leftist, socialist side, until June 1934 when on the Night of the Long Knives Hitler assassinated Ernst Rohm and the 85 Nazi leftist leaders. Few viewed what was happening in Austria and Germany with displeasure, as Livínov did, perhaps because he was a Jew and understood the seriousness of the racial laws that were being imposed. But the Soviet Union had been on the verge of war with Japan for years due to the invasion of Manchuria (the border with China), and it was impossible to sustain two war fronts. They were not to ally with Germany, but neither were they to support France and England.

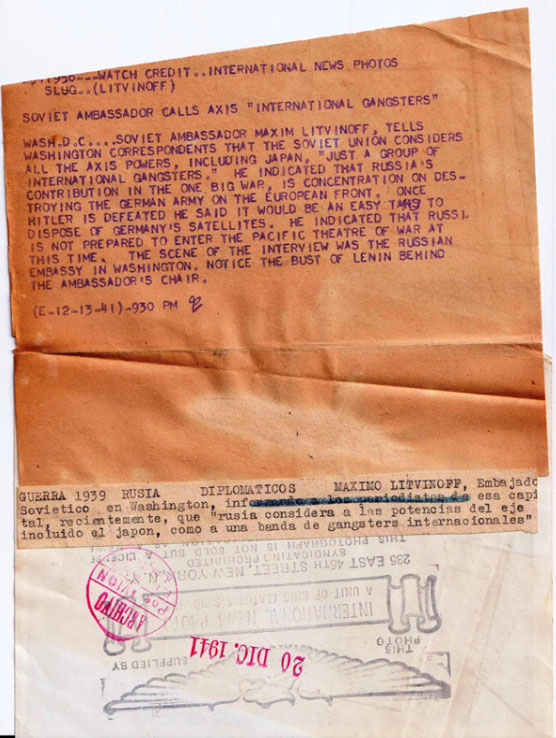

On this narrow path, he did everything he could to maintain a neutral situation, which is why he reestablished relations with the United States. But when Germany began to expand, decisions had to be made. By 1939 the war had started and at that time the hard line in Moscow was triumphing, Litvínov was stripped of his negotiating power and a pact with Hitler was demanded. But Hitler stated that he could not have relations with Russia if the pact was signed by a Jew.

On April 18, 1939, the senior staff of the Politburo appeared in his office with the presence of Laurenti Veria, director of the KGB, to demand his resignation and replace him with Viacheslav Molotov. His collaborators were arrested including the dismissal of Jewish diplomats and staff. Molotov was a Party man, a soldier, who looked askance at the outside world, and three months later he signed the agreement with Hitler and shortly after Russia invaded Finland as yet another imperialist country.

As expected, in June 1941 Germany advanced on the Soviet Union forgetting what was agreed. Litvínov, to whom they could not present any accusation, was appointed ambassador to the United States where he managed to send the weapons that helped to finish repelling the Germans.

Finally, the war -the Great Patriotic War, as the Russians called it- was much bloodier than perhaps it would have been with a peace effort -there were close to 33 million Soviet civilians and soldiers killed-, but that is a story counterfactual that we cannot do. In 1946 the so-called Iron Curtain rose, the Cold War began, which would last forty years in which the USSR closed itself off from the rest of the world, only to collapse when it opened up to it. Today Litvínov is claimed as the one who wanted to create a better world but was devoured by the internal monsters that ended up destroying the first great social project of the 20th century.

The set of photographs that aroused interest in sharing his story presents him to us in different diplomatic missions.

* Special for Hilario.