In 1875, Hermann Burmeister (1807-1892), former professor of zoology at the University of Halle and, since 1862, director of the Public Museum of the Province of Buenos Aires, published Los caballos fossils de la Pampa Argentina, a work printed by order of the government. It was intended to be displayed at the World's Fair in Philadelphia, an event that would take place between May 10 and November 10, 1876 to commemorate the centennial of the American declaration of independence.

The work was an initiative of Burmeister himself who, "Eager to see represented the Public Museum of Buenos Aires (so rich in fossil remains of the extinct fauna of South America) (...), I dared to propose to the Superior Government of the Province serves to decree a sum capable of covering the expenses of the publication of a work contracted expressly to describe and represent one of the most curious objects of said Fauna, so that those attending that exhibition form an idea of our scientific wealth.

Burmeister in 1874 had finished volume 2 of the Annals of the Museum, where, since 1870, he had been publishing a series of magnificently illustrated monographs dedicated to the glyptodons kept or exhibited in the institution. That volume had totaled more than 500 pages and had more than one disappointment, to such an extent that in its proem of November 1874 it announced the end of the series and something similar to a withdrawal:

“I am very sorry that the publication of this work has lasted four years, from 1870 to 1874; but the fault is not mine, but the insurmountable circumstances and mainly the need to send the drawings for the plates to Europe, to allow them to be executed with precision and elegance. It is true, there is no lack of lithographic workshops in Buenos Aires that work quite well; but the artists of these establishments are not accustomed to scientific works, and for this reason the proofs do not come out with the necessary perfection. But, by sending the drawings to Europe, not only a lot of time is lost, at least half a year for each delivery, but also the foreign artist lacks the author's inspection; many times he does not understand the drawings well, due to lack of knowledge of the object, and also sometimes due to the whim of the artist he works according to his own ideas, and not exactly according to the originals of someone else's hand. This has happened, that I have been forced to correct some plates, and even in the last installment there are quite serious errors of this kind in them.

To overcome all these impediments and others, which I do not wish to mention, one needs not only a hard and persevering character, but also complete health, capable of sustaining perpetual work, bothersome and incompatible with the true scientific occupation of the scholar, who cannot he has other interests than perfecting his works; mainly if the age of the individual is already close to years, where senescence begins and youthful robustness is lost. Touching myself with these years is not convenient for me, to work more in this way, being at the same time a sculptor, to restore the fossil objects of our collection; the next day a painter, to draw my own ready-made works, and send the figures to Europe; finally an author to describe them and watch over the impression no less difficult than the execution of the plates painted by another hand than mine. Due to all these circumstances I am forced to desist from the continuation of these Annals in the principled mode. I think, to be able to say, that I have worked enough, to finally rest on my works.”

He was then 67 years old, but not with the criticism that the young naturalists of the city and his compatriots based in Córdoba began to load on him and his work in the museum. Perhaps for this reason, he had to postpone the rest and undertake this new writing that, like any initiative of this type, reveals the necessary alliances to survive in the country's nineteenth-century science. More than as "a representation of the museum and the science of our land abroad", the "fossil horses" should be read as an expression of Burmeister's power against its potential competitors, be it fossil exporters and their friends from the Rural Society, the young people gathered in the Argentine Scientific Society (established in 1872), the German academics from Córdoba or the professors of geology and natural history from the University of Buenos Aires.

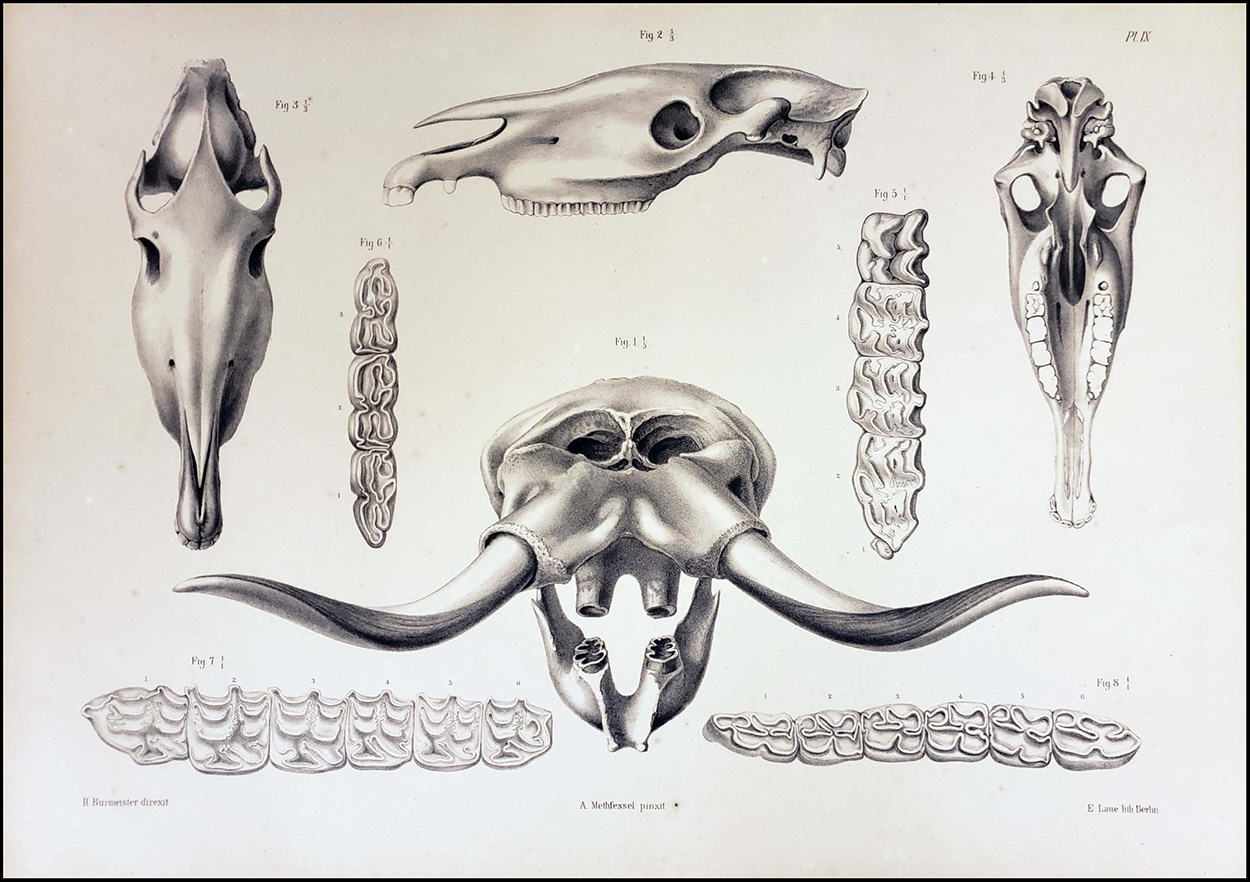

The proem of Los caballos fossils is a trotting walk through the names of the politicians who support the Prussian: Colonel Álvaro Barros (1827-1892), governor of the Province between September 1874 and May 1875, writer and founder of Olavarría , someone who recognized that, in those years prior to the so-called "Conquest of the Desert", the strategic weapon of the Indians was the possession of the horse. Barros, invited by Burmeister, toured the museum and far from being impressed by the megatheriums, the hairy giants, the mylodonts or the teeth of the prehistoric tigers, "he admired the difference and various curious circumstances when comparing the head of the fossil horse with that of the current, a comparison that he could easily make by the habit of examining many specimens of current horse skulls, in the bones scattered in our campaigns.”

Added to Barros' endorsement was that of his successor in office, Carlos Casares (1830-1883), son of a Spanish Consul, "enlightened gentleman, friend of the natural sciences and educated in his youth at a school in Germany", who In addition, he had dedicated himself to rural and commercial tasks. He was seconded by his ministers Aristóbulo del Valle (1845-1896), an art collector and reader of Darwin, and Rufino Varela (1848-1911), who with his brothers were founders and owners of the newspaper La Tribuna. There, in the newspaper's workshops, located at Calle de la Victoria No. 37, Los Caballos fósiles de la Pampa Argentina were printed, 88 pages in large folio, written in Spanish and German, accompanied by 8 lithographs drawn by Alfred Molet. and sent for their realization to the workshops of Carl F. Schmidt, the botanist and artist of Berlin. It is probably the engineer Molet, an expatriate and former student of the National School of Arts and Crafts (Arts et Métiers) in Châlons, a city in the Champagne-Ardenne region of France. If indeed it is the same Molet (1850-1917), at the time of making the drawings he must have been about 25 years old and he still did not know that he would establish a calcium carbide plant in the Province of Córdoba. Nor that, later, he would dedicate himself to the manufacture in Buenos Aires of devices for acetylene gas, when this, due to the fixity and clarity of its light, its calorific power, its ease of obtaining and its low cost, was used for generators, public lighting, mining lamps and lighthouses.

Carl Friedrich Schmidt (1811-1890), for his part, had specialized in producing botanical lithographs in collaboration with Otto Karl Berg, professor of plant medicine at the University of Berlin. Some think that he was the owner of the photography studio that operated with that name in Halberstadt, a city in Saxony-Anhalt. As it was, unlike the monograph on the glyptodonts, Burmeister resorted to a draftsman from Buenos Aires, but he sent the lithographic plates to Berlin to be made.

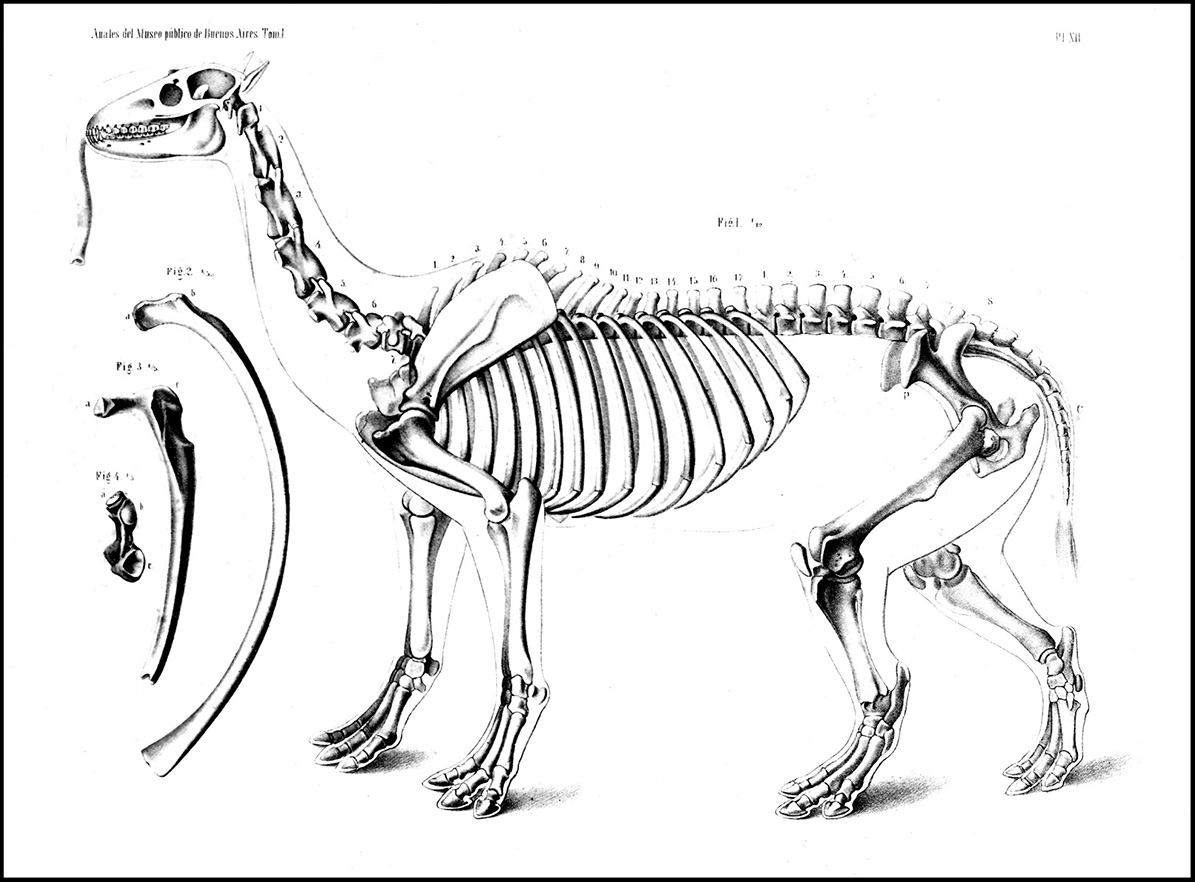

Apparently, it was Barros who had decided the subject of the work to write, to which Burmeister willingly agreed. The object was suitable because it spoke of the past, but also of the present of the "soil of our land": the conformity of this animal with the current one embraced all the parts of the body, even in the number of loose bones of the skeleton. With this, it was demonstrated that nature, "with a slight modification of the accepted type, was capable of producing innumerable forms, creating those abundant and surprising structures or conformations, which existed in remote times and still live on the surface of the earth, affecting its well-known variety.

Portrait of German Burmeister (1807 - 1892).

Burmeister left it to scholars of "lively and youthful imaginations" to speculate on the causes of this variety. He stopped at the pure and serious form of the objects convinced as he was that Darwin's doctrines would soon fall into the abyss of oblivion due to their dogmatic and anti-scientific character: "Science should not give credit to anything that is not proven with arguments convenient“- he affirmed, sure of himself, on August 25, 1875, ignoring –like Molet- that the future would hold something else for him.

* Special for Hilario.

Editor's note: For more information, consult the author, Florentino Ameghino & Hermanos. Argentine Company of Unlimited Paleontology (Edhasa, 2021) and, above all, El Desierto in a showcase. Museums and natural history in Argentina, written together with María Margaret Lopes (Prohistoria, 2014).