The actions of this gauchesco vate attacking Rosas with various publications of his poetry in the language used in both the eastern and the River Plate campaigns are well known. When Justo José de Urquiza, governor of Entre Ríos, made a statement on May 1, 1851 against the political and economic hegemony of his Buenos Aires counterpart, Juan Manuel de Rosas, many of his opponents soon approached him, among them Hilario Ascasubi.

A well-known poet and businessman, Ascasubi managed to build a fortune that linked him with many of the personalities of his time. But his family origins were very obscure. Already trying to get married in the 1820s, the mother of his fiancée, a lady named Zemborain, filed a dissenting suit against him for considering him of African descent, and she won. When he married in Montevideo his future wife, her family also made a similar judgment against him. But this time a more correct justice ruled in his favor.

Ascasubi tried to hide his true origins by writing in one of his numerous books that his father was of Spanish origin. And she could no longer hide who she was from her mother, since throughout the Río de la Plata it was known that she was the daughter of Dr. Joseph Eugenio de Elías, a well-known magistrate, and of a mulatto woman from Cordoba, as Father Grenón remembers in one of his numerous books. While only what he alleged was known about his father. A young genealogist, Eng. Francisco Martelli, has elucidated this mystery. Ascasubi's father was the grandson of slaves of the Canon of the Cathedral of Córdoba, Ascasubi. For those years, this origin meant total social damage. This explains the reason, unimaginable today, for the rejection that our famous poet suffered.

Having emigrated to the Eastern State for twenty years, the Pronouncement made on our Coast was a reason to place himself under the orders of Governor Urquiza, writing poems dedicated to the event that took place there.

As is known, Urquiza in the last years of the 1840s had made important progressive foundations, in line with the advances of the civilized world of that time. Among these works, and I believe that it is one of the most important at that time, the creation of a secondary school in the city of Concepción del Uruguay stands out, the now called Historical School that still remains a luminous beacon of knowledge. Prestigious personalities passed through it and held important positions not only in Argentina but also in several South American countries. Urquiza also summoned excellent teachers with whom he made that institute famous. But something little known is that he equipped it with a printing press, an unusual fact in those years. With it he wanted to influence the minds of youth with the ideas of freedom and republicanism.

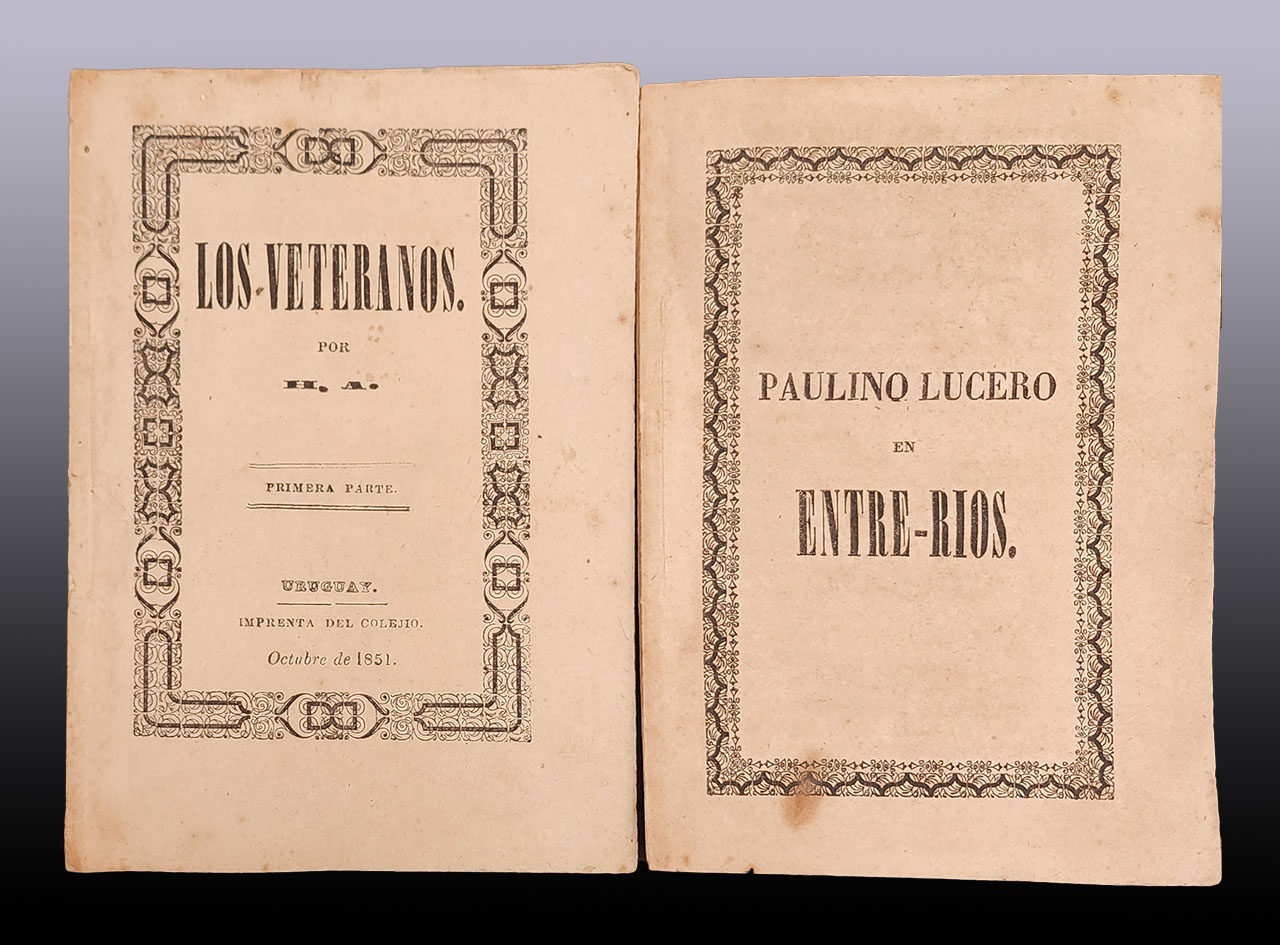

And it was in that printing press where Ascasubi, having already gathered Urquiza's forces, produced four pamphlets, now very rare, with gaucho verses in the form of dialogues with which he popularized the campaign against Rosas among the people, soldiers and gauchaje.

As I said, there are very few specimens that have reached our time. Generously distributed in towns in the Eastern State and the Buenos Aires and Entre Ríos countryside, they soon disappeared in the hands of careless readers.

The first time we saw them was at the auction organized by ALADA in October 1958, an auction held by the Bullrich House. Needless to say, they sold at a very good price and were acquired by well-known collectors of those years.

After much perseverance I was able to obtain three of them, at the same time that I discovered my relationship with their author through an unknown branch. Our poet hid his paternal and maternal origins, we already mentioned it. His father was not born in Spain as he alleged in one of his writings. His grandfather had been a slave of the Cordoban Priest Ascasubi. And his mother was the natural daughter of a mulatto woman with a student from the University of Córdoba who over the years reached prominent positions in the Buenos Aires judiciary. Hence her blue eyes and fairly white skin. But in his time everyone knew that origin that he unsuccessfully tried to hide. Hence also the dissenting trials that were filed against him the two times he tried to get married. In the first, which occurred in Buenos Aires, he lost; However, in the second the Montevideo judges ruled in his favor, claiming to be against racial discrimination.

But back to the brochures. They were printed at the College of Uruguay in 1851 and attack Rosas with virulence. The first one we can cite is “Urquiza in the new homeland, or the eastern gauchos talking in the mountains of Queguay on July 24, 1851” and is dedicated to General Eugenio Garzón. Unfortunately it has not been possible for me to obtain a copy. But it is known that it is a form of not many pages and of a similar size to the other three.

The death of Camila and priest Gutiérrez, a tragedy that moved locals and strangers.

The second pamphlet is titled “Thefts and lamentations of Donato Jurao or the death of the unfortunate Camila O’Gorman who, in the company of Priest Gutiérrez, were fiercely murdered in Buenos Aires by order of the famous and cowardly butcher Juan Manuel Rosas, titled Supreme Chief.” It indicates on its cover: By Hilario Azcasubi (sic). Uruguay. School Printing Office. (52 pages)

The other pamphlet has the following title: “The Veterans. By H. A. Uruguay. School Printing Office. October 851.” (40 pages)

“Paulino Lucero in Entre Ríos”, with its 40 pages, is the last.

All of them measure 15 x 10 cm, which indicates that they were printed in that size to be carried comfortably either by travelers or soldiers on campaign. Unfortunately, these measures facilitated its loss, as we have already indicated.

With this article we want to remember the almost unknown publications from the Colegio de Uruguay that were distributed in random circumstances in our History. They popularized the fight undertaken by our first elected president with the Constitution he organized, General Justo José de Urquiza, and our well-known gauchesco poet Hilario Ascasubi.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades