By Guillermo Vega Fischer

Cities constitute one of the most complex and wonderful constructions of human creation. In them our species displays its civility and capacity for coexistence, being also reservoirs of its cultural heritage, its technological development, its science and its art, they are also witnesses of its history. Every corner, every street and every square speak to us, sometimes with mute signs, of those who built them or wounded them in battles, and also of those who destroy them. Cities grow like palimpsests, those ancient manuscripts that, due to the lack of paper, preserve scriptures from different eras, superimposed one on top of the other. Those of us who live in this wonderful city of Buenos Aires, founded in 1536 and refounded in 1580, live with this multiplicity of times, almost five hundred years of history, in so few kilometers! However, this overlap sometimes leaves us with a bitter aftertaste, as it highlights the sad reality that later times almost completely erase the signs of those that preceded them. Pray in the name of advancement, progress or the future; pray in the name of a political color that annihilates the memory of its opposite. Or more in keeping with our time, due to laziness and ignorance, added to the unbridled real estate profit. And what we read in the books written just a few decades ago can hardly be found on the corners, in the streets, in the squares.

One of the most emblematic cases of these erased layers of history is that of the 1910 International Exhibition, held on the occasion of the centenary of the May Revolution. How is it possible that so few traces of the most lavish celebration that took place in our city and in our country survive?

Such a date found Argentina at the zenith of its economic development, and at a time when the great international fairs and exhibitions, which emerged in the mid-19th century as a result of the Industrial Revolution and within the framework of a liberal capitalist model, became imposed as the means of demonstrating the greatness of a nation. The Paris International Exposition of 1887, on the occasion of the centenary of the French Revolution, and the World's Fair: Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, United States, for the four hundredth anniversary of the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the New World, are two antecedents. The International Exhibition of the Centennial of 1910 should be at the height of those. Buenos Aires was at that time the largest urban conglomerate in Latin America, the eighth city in the world and one of the richest thanks to the agro-export economic scheme that had been developed since 1880. Argentina was called the granary of the world and in Paris they used to use the phrase Il est riche comme un Argentin! -in English, he is rich like an Argentine!

The Exposition adorned the city from May 1910 and some activities lasted until the following year. 35 new buildings specially designed for this festival were erected, divided into five major exhibitions: Agriculture and Livestock, Railways and Land Transport, Hygiene, Fine Arts, and Industry. Pavilions from different provinces such as Córdoba, Mendoza, Salta, Jujuy and Tucumán, and from friendly countries: Spain, Italy, England, Switzerland, Austro-Hungarian Empire and Paraguay were also erected. Some made of iron and glass, others made of concrete, each one was an architectural jewel inspired by the various avant-garde aspects of the moment, such as eclecticism and art nouveau. Can you believe us, reader, that only a handful of all these buildings remain standing, and practically hidden from view of the citizens.

In this article we will make a brief account of its pavilions and monuments to venture on a real journey through present-day Buenos Aires, in the footsteps of the Centennial International Exhibition. And we include it in the Cultural Walks section, then, as an invitation to tour the city, to be vigilant when crossing certain squares or traveling certain avenues; to do it with a curious look, if you want archaeological. As an aid, we will trace on a map of this metropolis the location of each sculpture, each monument, and even some slight vestiges of that Exhibition. And finally, in the desire to promote a call for recovery, preservation, in short, respect for our cultural, architectural, artistic and historical heritage.

Art Pavilion

Let's start with the Art Exhibition; Located in Plaza San Martín, it took as its headquarters the Argentine Pavilion that was designed and built in Paris on the occasion of the Universal Exhibition of 1889. Work of the Parisian architect Albert Ballu, the national government commissioned it to be dismantled and then transferred to Buenos Aires. He then designed a magnificent building in an eclectic style and made of iron, majolica and glass, which won first prize among international pavilions at that 1889 exhibition. Rebuilt in our country in Plaza San Martín, it originally had a theater on its ground floor, and was successively the venue for various cultural initiatives, such as the National Exhibition of 1898; two years later, the headquarters of the Argentine Products Museum of the Argentine Industrial Union; and in 1910, the venue for the Fine Arts Exhibition during the Centennial celebrations.

That exhibition was inaugurated by Mayor Manuel Güiraldes on July 12, 1910, in the presence of President José Figueroa Alcorta, among others. It included the Argentine Pavilion and other supplements, since it turned out not to be enough for the number of pieces exhibited, which reached a number of 2,375. After this use, the pavilion became the site of the National Museum of Fine Arts until its final demolition around 1933. In 2014, this old Argentine Pavilion made headlines again, since remains of its irons were sold in Mercadolibre by the heirs of the person who once bought them at public auction. What remains of this wonderful building?, the photographic record of the artists who posed their camera in that last decade of the 19th century and the first of the 20th, (VER) and the five sculptural groups that decorated its exterior, now distributed throughout the city.

The four sculptures that finished off the corners of the building were commissioned from the French artist Louis-Ernest Barrias. These were two pairs of sculptural allegories with masts, Navigation and Agriculture, and the central allegorical group, The Argentine Republic, the latter the work of the French sculptor Jean-Baptiste Hugues. All were cast in bronze by the prestigious French firm Thiébaut Frères, author in Buenos Aires of the lamppost that crowns the building of the newspaper La Prensa on Avenida de Mayo. These five works are preserved, and can be seen located in various parts of the city. The Argentine Republic was relocated to the Raggio Technical School, Avenida del Libertador and Pico, in the Núñez neighborhood (n.1 on our guide map). One of the copies of La Navegación is located on Avenida de los Incas and Zapiola in Colegiales (n. 2), the other, in Plaza América, in Villa Riachuelo. Unfortunately this figure is incomplete, the male character lacks an arm and his oar and the female character lacks his trumpet (n. 3). One of the copies of La Agricultura embellishes the Plazoleta Alejandra Pizarnik, on Avenida San Isidro Labrador and Avenida Cabildo, in Núñez (no. 4), while the second does so on Avenida Riestra and Martiniano Leguizamón, in Villa Lugano (no. 5).

Mast with a sculptural group La Navegación located in 1935 in South America Square in the Villa Riachuelo neighborhood of the City of Buenos Aires. This photograph was taken in 1952, when the work was transformed into an altar for the recently deceased Eva Duarte de Perón. Courtesy Photo File Américo Carpinetti.

Returning to the matter of these fateful demolitions, could this building, the Argentine Pavilion, have endured and be of use today? Yes, an irrefutable truth confirms it. Its pair, the Chilean Pavilion of the same Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1889, also designed in the industrial style of iron and glass, is today superbly installed in Santiago de Chile, and is home to an interactive museum, the Artequin Museum.

Industrial Pavilion

It was located in the woods of Palermo, between Libertador Avenue (then Vértiz Avenue), Iraola Avenue and the lakes. The set of industrial pavilions was only inaugurated on September 25 of that festive 1910. It was designed by the nationalized Argentine Uruguayan architect Arturo Prins, the same as the unfinished neo-Gothic building of the Faculty of Law on Las Heras Avenue, currently the Faculty of Engineering. The main building was semicircular, in art nouveau style and with a lighthouse. As in each section of the Exposition, the industrial fair had a large number of pavilions, warehouses, machinery galleries, private pavilions and eight of the provinces present. All these constructions were demolished, however the semicircular profile of the main building survives in the design of the current Plaza Holanda, this being the sixth point on our map (n. 6), in the search for the traces of the Great Exhibition.

Plan of the Industrial Pavilion. Observe when comparing with the following photograph, taken from an airplane some time after the Centennial Exposition, how Holland Square maintained the semicircular design of the main building.

Agriculture and Livestock Pavilion

It was located on the land of the Argentine Rural Society in the Palermo neighborhood, added to a property previously occupied by the old Infantry Barracks, the block between Alvear, Sarmiento and Cerviño avenues. At the end of the Exhibition, the Plaza Seeber was inaugurated in this venue, which commemorates the Mayor of Buenos Aires who brought the Argentine Pavilion from Paris.

Contrary to the rest of the sections, several buildings of the Agriculture and Livestock Pavilion are currently preserved, and all in magnificent condition. The Argentine Rural Society began in 1906 the planning of the works for the Centennial Exhibition. Architects Pedro Vinent, E. Maupas and Emilio Jáuregui were entrusted with the construction of the Emilio Frers Pavilion, which housed the Agricultural Museum. With eclectic academic features and art nouveau in its blacksmith shop, it was built in masonry and with large iron windows and scattered glass, and it has 2,350 square meters. The architects Eduardo Lanús and Pablo Harry (the same ones who built the Customs building on Azopardo street) were entrusted with the creation of the El Central Restaurant and the Official or Honor Tribune, and the architect Salvador Mirate with the great central court of 3,280 square meters and the Equine Pavilions, lateral to the central court, in an industrial style, with laurels and other decorative motifs on the outside. These equine pavilions were -and are- crowned by various sculptural groups, works by the French artist J. Vaisseaux and the Italian Giovanni Bertini and made of cast iron -hence the reddish color they currently have- by the French firm Duval. The woman represents the land, the sickle refers to agriculture and the man, surrounded by animals, to the peasant.

Let this set of buildings be the seventh point of our promenade. You can walk in front of the imposing Frers Pavilion on Santa Fe Avenue, or on occasions such as the recent Rural Exhibition or many other activities on the property, walk through this space, the closest that remains to the one that the stunned eyes of the porteños saw in 1910.

The Frers Pavilion today. However, since it is the only pavilion preserved with integrity, significant losses or remodeling can be observed. The ceilings and the glazed dome, a sculpture and its pedestal over the entrance -and its peer on the inside of the building-, the lower part of each walled-up window, and the simplification of its ornamentation.

Railway and Land Transport Pavilion

The largest of the exhibits was the Railways and Land Transportation. It was inaugurated on July 17 on the grounds of the 1st Patrician Regiment. European automobiles, yachts, rowing sports boats, airplanes, locomotives -like the first one that circulated in Buenos Aires in 1857, La Porteña-, carriages, one of them presidential, wagons, fire trucks and steam and electric motors were exhibited. The magnificent pavilions of the participating countries (Italy, Great Britain, Germany, Austria, the French section and Argentina) were erected on the great site, each one built by workers from their respective nations. It had two railway stations, one made in Italy and the other in Argentina. One of them was later sent to Santa Fe as the head of the North Central Railroad. This turned out to be a large amusement park. The Newbery brothers had organized rides and races in hot air balloons, for this purpose they used four balloons, arranged in pairs on each side of the central Plaza, while a cable car crossed the property from the Great Britain pavilion to the German one.

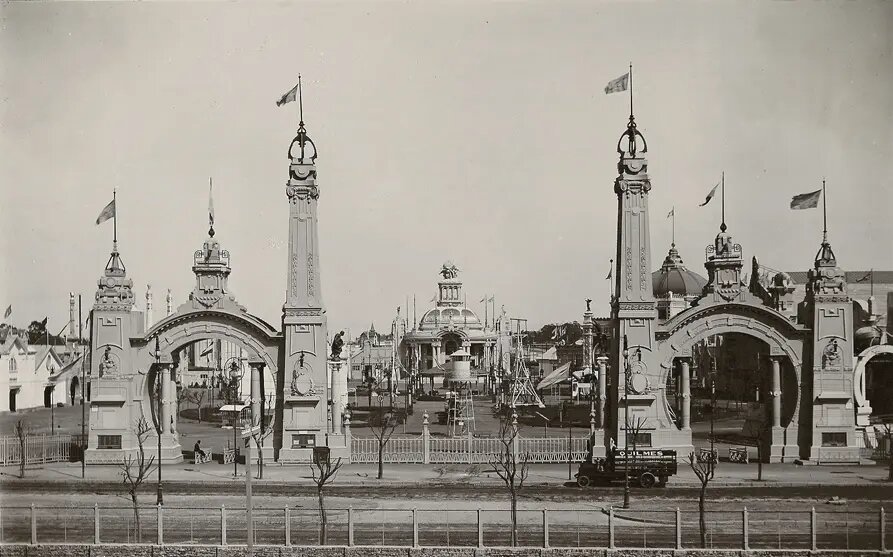

It was the most attended exhibition. Visitors entered through two large circular portals that framed the entrance and faced, in the distance, the true jewel of this exhibition, the Argentine Pavilion, also called "Great Central Pavilion of the International Railway and Land Transport Exhibition" or "Pavilion of Festivities, Post Office and Telegraphs". It was designed by the Milanese architect Virginio Colombo together with the Vinent, Maupas and Jauregui studio, of which Colombo was its director, having just arrived from Italy and for which he won the gold medal. Virginio Colombo was one of the most important architects in Buenos Aires in the first two decades of the 20th century. He arrived in our country in 1906 hired to decorate the Palace of Justice, and since then he has embellished our city with works in the Milanese Liberty style, one of the currents of art nouveau.

The Argentine Pavilion and in front of a multitude of attendees to the Exhibition of Railways and Land Transport, the most visited of the Centennial.

Let us now return to the Argentine Pavilion, its style is academic eclecticism and the ornamentation shows influences from the so-called Viennese Secession. The curved front, in the form of a hemicycle, has a gallery supported by large columns and a large glazed dome on top. We write in the present tense, because miraculously, this Pavilion still remains, although in a complete state of abandonment. Its particular location, within the military premises of the Patricios Regiment, does not allow us to visit it, but it can be seen from above, going up to the garage on the terrace of the Jumbo Easy Palermo, whose entrance is on 345 Intendente Bullrich Avenue. This is our eighth point on the map.

His story is very particular. Many young men from Buenos Aires know it since the revisions for compulsory military service were carried out there, and since its suspension in 1995, the building was completely disused and at the mercy of God. In 1994 the Army signed an agreement with Cencosud, a Chilean multinational business consortium, for the exploitation of the land for twenty years, with an extension of two sixty-month periods. The great hypermarket that we mentioned was built there. One of the conditions of the agreement required the company to carry out the "recycling of the Great Central Pavilion (...) until achieving a degree of completion similar to that which it originally had, including the maintenance of its exterior facades, ornaments and related devices." Of course, the restoration and maintenance never took place. Cencosud designed a "Value, Restoration and Recycling" project in 2008, which did not materialize either, which led the National State to initiate a lawsuit against the company (file 29,528/2014). In 2010 the Pavilion was declared a National Historical Monument and in 2017 the State Assets Administration Agency announced that the property would change its functionality. Through a decree signed by former President Macri, the land was enabled to transform it into a public space with private enterprises, once the contract with Cencosud had ended. The "National Ideas Competition for the Centennial Pavilion and its surroundings" was launched, and in 2019 the winner was announced, whose project includes the construction of buildings for homes, offices and premises, and a large park with the Argentine Pavilion as protagonist. Pandemic and crisis through, the plan remains inert.

As we write this article, we are reading some happy news: the Supreme Court unanimously rejected a proposal presented by the company Cencosud against the sentence that ordered the restoration of the Pavilion. Chamber V of the National Chamber of Appeals in Federal Administrative Litigation -upon confirming the judgment of first instance- upheld the lawsuit and ordered that Cencosud "proceed with the restoration of the Great Central Pavilion until achieving a degree of completion similar to that originally owned, including the maintenance of its previous facades, ornaments and related devices, with costs”. The Court held that the decision "is in line with the text of article 41 of the National Constitution, which recognizes the fundamental importance of preserving the historical, artistic and cultural heritage of the Nation." The reports used by the Court show the high level of deterioration and risk of the protected complex, both outdoors and indoors, detailing that the Pavilion no longer has its upper part, that its walls have cracks from which bushes emerge , that the glass is broken, the plaster and ceilings are sagging, the columns have holes and their interior iron structure and wooden floors are almost completely absent. !! Congratulations!!

We conclude here the first installment of this historic walk that includes eight points to visit or schedule, since it will be completed in the next issue of this publication with the exhibition that remains to be pointed out, that of Hygiene, and the various monuments, gifts from the friendly countries and their communities in our country, and others of their own construction. Winter is coming to an end and the city awaits us to rediscover it from this perspective, a mix of tourism and urban archaeology.