The good news motivated us to write an article to share with our readers. In this plan, we virtually interviewed the protagonist, Dr. Milda Rivarola, and we asked Dr. Ticio Escobar, two referents of cultural Paraguay, for her opinion. With the interview, we put together the text and we thought to incorporate into it the concepts of the researcher and reference from all over Latin America, but when his response reached us, the content was of such a hierarchy that we decided to publish it independently, since it is a mini essay of great importance. it was worth.

THE SMALL PLOT OF HISTORY

By Ticio Escobar

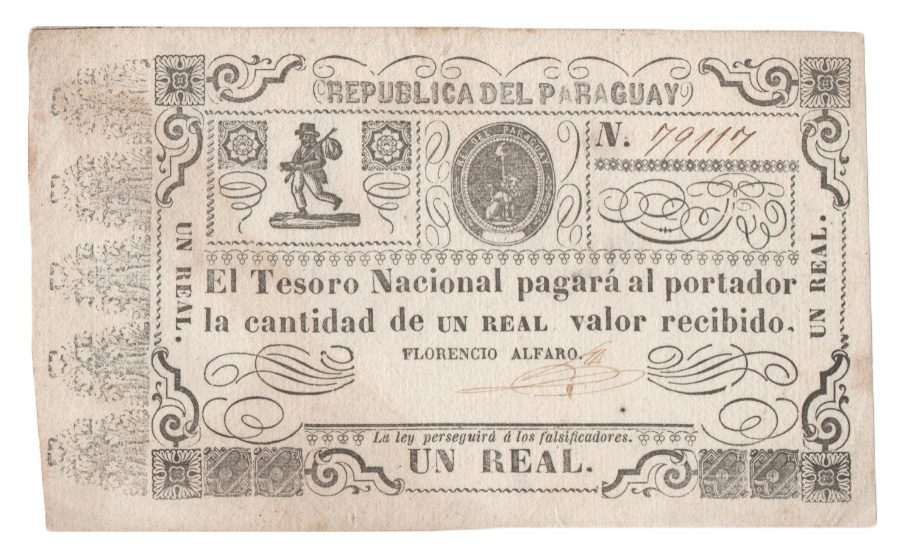

In our country - Editor's note: the author, a Paraguayan expert, refers to his country - many, too many, people appropriate important public assets to enrich their private assets. Others, few, carry out the opposite movement: they put valuable private goods at the disposal of the public use. Such is the case of Milda Rivarola who, apart from having formed a fundamental library, for 40 years has been collecting maps, engravings, photographs, postal letters, coins and essential documents for the study of the history and, in general, of the culture of the Paraguay and the region. Classified and referenced according to relevant criteria, this collection of almost 3,000 pieces circulates free of charge through a website called Imagoteca.com.py.

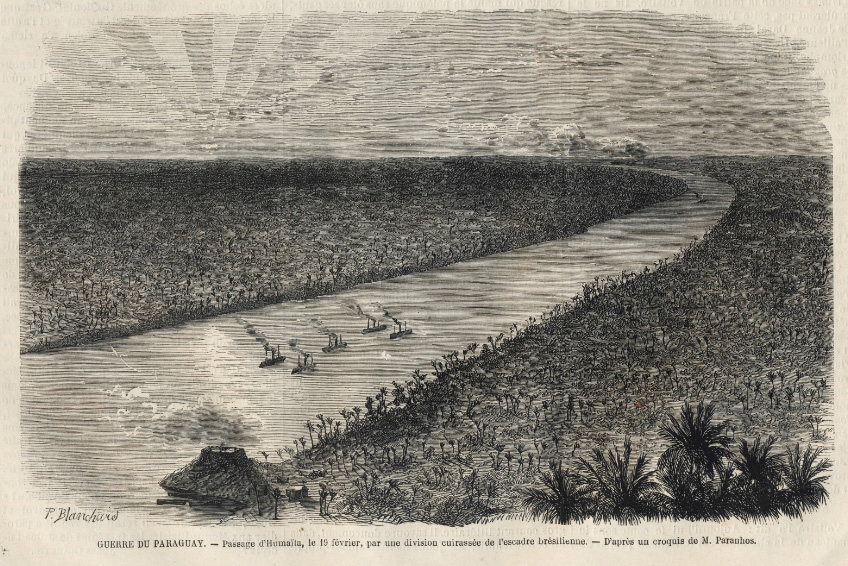

The patrimonial and editorial criteria that guide the formation of the collections and their presentation lead me to some reflections related to the scope of my work. Given the extensive and varied nature of the material, I confine myself to photography, aware that what has been said in relation to this field can be used to face others, especially that corresponding to engraving.

It is significant that this program is developed under the invocation of the image, a primary component, although not the only one, of the collection. Outside of the omnipresent soft aestheticism of the image, promoted by the society of advertising, information and the spectacle, the image is assumed in this collection in its possibilities of connecting with its own time and bringing closer indications of realities that escape the documentary record. The author of the collection says that traditionally the image was not considered as the source of history; only since the 1930s has it been used as an illustration of texts. Photography serves today, and that is clear in this collection, not only as an illustration of the contents developed in the text, but as a device to enrich history, aesthetics and anthropology, as in general social theory, with the marks of the time, the out-of-frame suggestions and the clues provided by the representation of actors and scenes omitted by the official history.

What is the reason for this change in the valuation of the image as a historical source? Basically the micropolitical approach that, without leaving other perspectives, Milda Rivarola incorporates: history does not only grow with the big names, the epicist record and the stories of the struggle for power and the conquest of rights. It also grows, and above all, with the movements of subjectivity and affections and with the thrusts of the creative imagination. Finally, it grows with the pressure of the unconscious and desire on the collective memory. For this reason, this collection treats with special attention minor scenes, daily tasks and occupations, common, anonymous faces and records of the diverse ways of living, thinking and feeling. It shows circumstances and characters traditionally considered in a picturesque key, generally discarded by official history: the world of childhood, the role of women and various scenes of indigenous people, peasants, immigrants and workers in charge of modest trades.

The change in perspective relative to the scope of the image rethinks, on the one hand, the links between the photo-illustration and the photo-document and, consequently, the relationship between the register and memory and the ups and downs between the micro and the macro history. On the other hand, this change makes it possible to relax the limits between documentary photography and aesthetics: the most "objective" of representations is always marked by figures that come from outside photography and which, in turn, show details that the sensitivity of the photographer and of the gaze could detect beyond what enables the pure technique. Finally, the representation and staging of social agents made invisible by the hegemonic gaze constitute, according to the thinker Jacques Rancière, the founding political gesture.

Milda Rivarola assumes these various possibilities and leaves them freely available to researchers, teachers, students and those interested in general in history and its interstices. This contribution is essential: it not only provides valuable and largely unknown information; it also directs the gaze towards the intimacy of the collective plot and thus allows enriching the social analysis with data from small history and living differently.

MILDA RIVAROLA, AN EXAMPLE TO FOLLOW.

In general, every collector imagines a horizon for his collection: it will be followed by a descendant, it will be donated to a public entity, it will be part of a museum created by said collector, it will return to the market through an auction house or a specialized professional, gallery owner, antiquarian, bookseller ... Or, as the Paraguayan historian Milda Rivarola (Asunción, 1955) has resolved, it will be part of a virtual space available to the whole world.

We became aware of this initiative and immediately contacted Dr. Rivarola -historian, sociologist and agricultural engineer- to learn the details of her proposal. "Paraguayan Imagoteca", that's how she called her website, already includes more than three thousand images -photographs and engravings-, six hundred maps, nine hundred postcards and a numismatics section; a heritage of free use -even for its reproduction-, since it is only required to cite the source.

As a researcher, Milda Rivarola has a specialization at the School of Higher Studies of Social Sciences in Paris, and a postgraduate degree at the Institute of Pan-Iberian Studies of Spain. She is a member of the Paraguayan Academy of History and founder of the Association of Paraguayan Studies. She has published dozens of texts on the social and political history of her land. With meager resources, she started her collection by buying what she could back in 1983, and since those initial collections, she never stopped. Today she has one of the most complete heritages on the iconographic history of her homeland in private hands and in many of these works, her copy is the only one preserved in Paraguay.

Committed to her work as a historian, she highlights the value of these reservoirs and in a decision that distinguishes her, she offers it to the community, to her research peers and to the ordinary man she wishes to investigate in her own identity. An example that should inspire other similar initiatives throughout America.

Collector and historian

HILARIO: You are a researcher committed to the culture of your country. At what point did she start as a collector or, rather, at what point did she perceive herself as a collector?

MILDA RIVAROLA: The stay in Brazil and in European countries (France, Spain), in the 1980s, opened my eyes to the voluminous iconographic material that exists about Paraguay, but which is very difficult to access within the country. It coincided with a change in academic and professional orientation, from sociology to history.

Collectors are obsessive people, with an insatiable passion. I suppose that we perceive ourselves as such as our collection increases, qualitatively and quantitatively. And it is completed (if that is possible) in certain areas prioritized by our interest. But it is a long process, it can take a lifetime.

H. With always little efforts from our national states, on what plane do you see the need to promote a virtuous relationship between public and private collections?

MR: In States that hardly invest in cultural funds, such as Paraguay, the role of bibliophiles and collectors is almost substitutionary, we are forced to do what the public sector does not assume as a function. And invest in the creation of museums, libraries, video libraries, image banks.

Once these private collections are completed, the States should establish protection measures, avoid their destruction, loss or forgetfulness in the future. Which, incidentally, is the great concern of every collector. I am not referring to expropriating measures, but to legal instruments -type leasings- that allow the continuity of these cultural funds, and their access to the interested public.

H: There is a general opinion among collectors that they remember the non-acquired work more than some that are already part of their collection. Do you also mourn the unincorporated works?

MR: There will always be maps, or engravings, or photos, whose existence we know of from a reproduction published in books or magazines, and which we never find on the market. Even now, it has become global with the digital tools of the internet.

Sometimes there is luck. In my student days, at the Paris National Library, I saw a beautiful full-page metal engraving of two Toba women fighting each other. I didn't even register the source, at the time. But she still kept that image in her memory. Four decades later, the engraving came into my hands, almost miraculously, when I acquired a series of dozens of articles from 1884/9, from a French expeditionary in the Chaco. I thought then that the pieces also seek their collectors.

H: We have been informed about a happy decision taken by you, that of creating the Paraguayan Imagoteca with your heritage. You can tell us how this idea was born, since there is no doubt, it requires a firm will and a resource strategy to be sustained over time.

MR: The decision came with the forced confinement of the pandemic. By being based on images, with paper support, in recent decades it had already taken care to gradually digitize this collection, and to index it as a measure of personal record. And the biggest investment, that of finding and acquiring those originals, had already been made.

There is also the wonderful resource of digital technologies. Historians are more trained to use written resources (from archives, libraries) than visual sources. Which implied new personal learning (supports, identification of signatures / authors, printing techniques, artistic schools, etc.). And I understood that those thousands of images constituted a kind of cultural heritage, inaccessible until now in Paraguay, that should be offered to all people.

H: Finally, how does the public access the Paraguayan Imagoteca ?, and we ask it from the perspective of those who will be able to dispose of its collection for studies and to expand knowledge, and from the perspective of those who, realizing that their assets will be preserved there. works, decide to donate to increase the patrimony of the Imagoteca.

MR: It is a portal, www.imagoteca.com.py, open and free. The search engine can be used to explore topics, or go "turning pages" of each collection, the one of cartography, postal letters, engravings, photos, numismatics, etc.

It remains to be noted that it is an unfinished task, due to its very nature. Every week I am raising new images recently acquired, and I still have to collect thousands of "secondary" photos, those published in texts of travelers, explorers, diplomats and scientists, from the 1880s to 1950. It is a way to continue giving life to that project.

Milda Rivarola's titanic task.