By Ana Martínez Quijano

If we look at art through the eyes of collectors who have dedicated their lives to bringing together a set of significant works, such as the Emperor Hadrian, the Medici or Catherine of Russia; if we then take a leap in history to discover the cares of the Guggenheims, the Rockefellers, Gertrude Stein, Paul Mellon or the Ganz, and we get to see the works of the British publicist Charles Saatchi, an advertising magnate turned marcher who put on the young British people who promoted in the spotlight and scandalized the world with their sensational displays, we will discover an exciting world that is not always accessible to the general public.

Fedor Rokotov (1735 – 1808): Catalina II. Retrato de Catalina la Grande (1729 – 1796), emperatriz de Rusia desde 1762 hasta su muerte. Con la colección de su esposo Pedro I el Grande y la suya, fue la creadora del Museo Hermitage, de San Petersburgo, uno de los más bellos del mundo.

The figure of the collector, sometimes visionary, arouses an interest that grows over time, in the same way that the appreciation for the collections that increasingly are a source of personal and social pride increases.

Art is what truly matters, what is enduring and what comes first, however, collectors play a leading role. There are collectors who stand out for their intuition and others for their extraordinary experiences; there are those who went down in history for the intelligence of their proposals or the theses that support their ensembles, for the extreme radicality of their choices, or for the fervent attention they devote to their possessions and to the artists in whom they believe and place their faith.

In short, in its most diverse incarnations, collectors marked turning points, contributed to change the way of appreciating art, seeing it, displaying it and pricing it, and some even knew how to weave the fabric that leads an artist to glory.

Behind each great collection there is a personal story hidden, and today - perhaps without knowing it - some design the foundations of the collecting of the future.

But who are these characters and what is the desire that guides them?

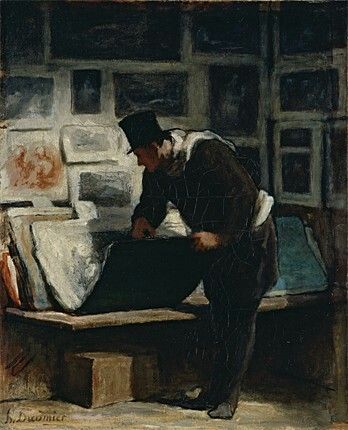

From the beginning of collecting, issues such as taste, audacity, the desire to surround oneself with beautiful things, passion or knowledge, began to make a difference. Balzac claimed that collectors are the most passionate beings on earth, but a tour of international and Argentine collections reveals that art is treasured for very different reasons.

From pure aesthetic pleasure to investment, there are many variants. The fan is inexhaustible: it goes from the silent collector to the one who behaves like a star of the show; from which he delegates the selection of his purchases to a curator, to which he imposes his personal taste; from the one who enjoys showing and sharing his artistic treasures, to the miser, who keeps everything for himself, and from the one who falls irresistibly in love with a work and makes every effort to possess it, to the one who only pursues social advancement or success. economic profit.

Each collection is an entity unto itself, with meanings that can be discovered and analyzed. It should be taken into account that the collector is usually an active cultural agent, capable of preserving works that on occasions (as happened with many of those exhibited at the Di Tella Institute), ended up being destroyed because the artists had no place to store them, or because the institutions were not interested in preserving them.

Until very recently, critics were concerned with art and artists, and in a distant place were collectors. Now, these figures, whose power is increasing, occupy a crucial space in the art system, because they defend the artists who collect tooth and nail, they see that museums legitimize the value of their works, they support their exhibitions and the publishing of books and catalogs.

A walk through the history of collecting will take us to Rome, Paris, New York, London, Houston, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Basel, Buenos Aires, Shanghai, Rosario and Córdoba, among other cities in the world.

How do you start a collection? Is it an activity only for the rich? What characteristics make the collections so different from each other? What bets are in each of them? How do they influence our way of appreciating art? Is it true that art opens all doors? Questions and more questions that deserve numerous reflections and answers, although we should first think about whether contact with art, in addition to giving people's lives a special shine, favors new forms of human coexistence, by revealing the overwhelmingly broad existence of others. worlds and other kingdoms, of situations and moments very different from those that we already know, that are to be discovered.

Never like today has art radiated so much positive energy. Those who question this condition can observe the expansion of the art world in the museums, galleries, fairs and biennials filled with collectors that multiply throughout the world.

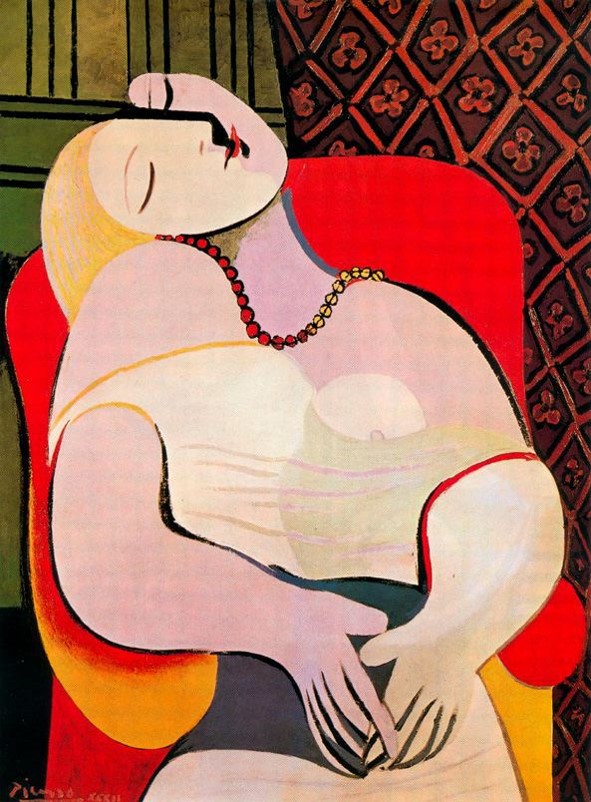

The conviction that artists are capable of producing visionary works, works that modify the way of perceiving oneself and of perceiving the world, is a concept that many share. The certainty that art has much to say is close to the position taken by Arthur Danto, when he quotes Brenson, an art critic for the "New York Times", who observes: "A great painting (of course, the term can and should be understood in a broad way, applicable to other genres) is an extraordinary concentration and orchestration of artistic, philosophical, religious, psychological, social and political impulses and information. The older the artist, the more he turns each color, line and gesture into a stream and a river of thought and feeling. The great paintings condense moments, reconcile polarities, support the faith in the inexhaustible empowerment of the creative act. As a result they inevitably become emblems of possibility and power. […] Spirit is embodied in matter […] It not only makes an invisible spiritual world appear to exist, but it appears accessible, within the reach of anyone who can recognize the life of spirit in matter. The painting points towards the promise of healing ”.

It is worth remembering that, although for centuries the monopoly of the distinction granted by good taste and the possibility of seeing the world and humanity with an eye educated by art, were assets reserved for a few, today, As Arthur Danto puts it so well, art has become the object of desire for “thirsty crowds”, who go in search of the ineffable.

Malba turns 20 and Costantini celebrates it with a new gesture

Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires (MALBA), reservoir of the Costantini collection. Photo of the Government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires.

Argentine collecting has a long and noble tradition. Since the end of the 19th century, in addition to collecting stupendous works, collectors such as the Guerrico family have demonstrated their educational eagerness and the desire to share their artistic treasures with Creole society. This spirit, far from being lost, endures. It was increased at that time with the participation and encouragement of critics and the press, who spread the presence of the collections in galleries and institutions. The art gathered by Aristóbulo del Valle, Rafael Crespo, Ignacio Acquarone, Adela Napp de Lumb, Victoria Aguirre, Antonio and Mercedes Santamarina, Francisco Llobet, Domingo Minetti, Luis Arena, Ignacio Pirovano, Augusto Palanza and Otto Bemberg; the González Garaño brothers, the Hirschs, Bonifacio del Carril, María Luisa Bemberg, among others, contributed to forging the Argentine taste and, on occasions, the heritage of our museums.

Meanwhile, and although in the 1950s the Torcuato Di Tella collection gained visibility, the social desire to share aesthetic emotions faded. The display of wealth was considered a sin.

It was only in the 90s that a more receptive public emerged, as well as a collection interested as never before in art. The superlative growth of artistic activities and the rise of museums was symptomatic of the ever closer communication that was established between collectors, artists, critics and the public.

Eduardo Costantini arrived at collecting, imposing a new style of high visibility, closer to that of the Americans than to the Argentine profile. In the 70s and 80s, almost until the middle of the 90s, the general tendency in our country was to hide the art that was treasured. Among the most important collectors in the world, even of impressionist painting, which is the most valued, there are several Argentines. But the moderation of Nelly Blaquier or Jorge Helft prevailed in Argentina. Until Costantini arrived and it became a success. His purchases at open-face auctions and the decision to pay record prices for the art that he had in his sights, consolidated his fame in the artistic environment and his name transcended the border.

With his socioeconomic vision, Costantini saw Latin America in the 90s as an emerging region, and in this way he became interested in his art. Thus he changed the focus of our largely dependent culture, loving European art, to value its own.

When the collection exceeded one hundred works and international institutions began to demand it for exhibition, the idea of founding a museum came naturally. And at first, when the building was under construction, it was difficult for the porteños to understand the collection: Who is Di Cavalcanti? Who is Covarrubias or Agustín Lazo? The palisade of the museum dawned one day with gigantic reproductions of the paintings of Antonio Berni, Frida Kahlo and Pettoruti. Who is Costantini? Soon, the appeal of the paintings of Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Tarsila do Amaral, Portinari, Xul Solar, Berni and other stars of Latin American art, conquered an audience that was not long in coming to stay.

Today, after more than twenty years, the collector shows that he knew how to keep his ideas and his word. To begin with, by putting a limit on the right of private property of art: "The owner of a work of art is nothing more than a transitory depository of a good that, in short, has public value and that sooner or later becomes part of the heritage of museums, that is, of the public ". The gesture was inspiring for Amalia Fortabat, who, without wasting time, bought a piece of land in Puerto Madero and began to build her own museum.

Museo Fortabat – Colección de Arte Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat. Buenos Aires. Obra del arquitecto Rafael Viñoly, fue inaugurado en 2008. Reúne en sus salas la colección formada por la inolvidable Amalita. Entre otras joyas, posee obras de Turner, Marc Chagall y hasta un retrato de la empresaria argentina, realizado por Andy Warhol en 1982. La pintura argentina reúne sus firmas más reconocidas, como Fernando Fader, Lino E. Spilimbergo, Xul Solar, Antonio Berni, Emilio Pettoruti y tantos otros. Foto de Nicolasrnphoto.

Costantini had broken the ice, and her example stimulated social participation. Through these years he was concretizing his plan. He moved his foundation from the family framework to a more open one, with public impact. Thus he donated the Museum whose value is estimated at 300 million dollars. The determination to hand over the Malba to society, formulated before its inauguration and repeated in recent years, surprised everyone. Who could imagine, in a country where words falter and people cling to what they have, that Costantini would end up giving up not only ownership of the most precious asset that he managed to create, but also dominance?

To understand the magnitude of the word "donation," one must remember the names of a few collectors mentioned at the beginning of this text. They went down in history.

A new example of the separation that Costantini established between his heritage and that of Malba, can be seen in the last purchase at Sotheby's, where, true to his old style and Latin American art, he bought a set of works for which he paid 25 million of dollars. But his destination is the Costantini collection.

A large part of these 21 works that, of course, will be exhibited at the Malba, remained in private hands and have not been exhibited for 30 years. Among them, the paintings by Wifredo Lam and Remedios Varo, reached record prices. The surrealist poet and painter Alice Rahon, Vicente do Rego Monteiro, Victor Brecheret, the Cuban Mario Carreño and the Argentines Aída Carballo and Facundo de Zuviría, make up this group. "It is very difficult for this type of superlative works to appear on the market and when they do, I try to buy them because it can take fifty years to see them again," observed the collector.

Note:

1. Reader of our virtual newsletters and kind interlocutor of our analyzes on the art market, the author sent us this text so that we would have it available. In the first section of it, Ana wrote it as a reference framework for her classes at the University of Salvador, being she the holder of the Art and Media chair in the Career of Management and History of the Arts. We share it with you to open the space for reading and reflection, but with an "update" made by the author of it, now exclusively for Hilario.