At the time of publishing this article, we are about to go through the first centenary of the death of William Henry Hudson who went into silence on August 18, 1922. Perhaps it is time to remember him as Rabindranath Tagore did, the Hindu, who He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913. As soon as he set foot in the port of Buenos Aires in December 1924, he asked the journalist from the newspaper La Nación, Carlos Alberto Leumann, to tell him about one of “his favorite writers”, the Argentine Guillermo Enrique Hudson. As happens today to a large part of Argentines, our compatriot had to admit his ignorance on the subject and hastily consulted Victoria Ocampo. The director of Sur, also declared herself incompetent in the matter, but she resorted to one of her main advisers, "Georgie".

Jorge Luis Borges introduced her to the life and work of that author he had referred to for the first time in "Queja de todo criollo" (in Inquisiciones, 1925), where he lamented the inevitable decline of gaucho culture and the Argentine Creole identity saying: "In Hernández's poem and Hudson's bucolic narrations (written in English, but more ours than a pity) are the initial acts of the Creole tragedy." In 1926, Borges mentions Hudson again, this time in a much more relevant way. In The Size of My Hope, that Creole book of essays that he would regret many years later (refusing to include it in his complete works), Borges refers to Hudson in the articles “The pampa and the suburb are gods” (where he cites Darwin significantly through Hudson and calls the latter "very Creole and born and raised in our province", and "La Tierra Cárdena", this is the first review of a literary work of the naturalist. In the year 1941 he would reaffirm his thinking by write in the newspaper La Nación “The Purple Land is one of the few books that bring us happiness.” The great Borges who had read Hudson in English, his original language, had enough authority to begin to introduce this unknown Anglo naturalist -Argentine in the canon of national literature. The article in La Nación would be reproduced and expanded in "Other inquisitions" of 1952.

William Henry Hudson or Guillermo Enrique Hudson, "Dominguito", as the countrymen of Quilmes called him, or "Huddie" as his intimates called him in England, was born on August 4, 1841 in the "Vineticinco Ombúes" estanzuela, currently located in the district of Florencio Varela, province of Buenos Aires, and which is the museum that bears his name. The Pampas plain was not only the area where he grew up, along with his five brothers and their North American parents, but it was also the source of inspiration for much of his work. He left Argentina at the age of 32, heading to England for several reasons: A bit for health (he had had a condition at the age of 15 after severe bronchitis caused by getting wet during a storm that caught him riding), the desire to achieve his vocation as a naturalist, which in the post-Rosista environment of Argentina had no future, and perhaps, to distance himself from a frustrated love, something similar to what happens to the protagonist of the Purple Land, Richard Lamb, for many his alter ego. With varied and solid motives, he chose the land of his ancestors, England.

He arrives in 1874, after a long trip aboard the steamship Ebro, a trip he shares with Abel Pardo who, in 1884, translated "Pelino Viera's Confession" (The Cornhill Magazine, 1883), which will be published in the newspaper La Nación de Buenos Aires. Aires on January 11 and 12 of that same year as "The confession of Pelino Viera", this being the first work by Hudson translated into Spanish.

His stay was hard from the beginning. A year after living there, he married the owner of the boarding house where he lived, Emily Wingrave; fifteen years older than her, he will be her “companion of hers” until her death in 1920. In England he exchanges the horse (which he will miss all his life) for the bicycle or walking. He hates the car and chooses the train to visit some towns that will put him in contact with the English hills, vaguely similar to the pampas, and chat with peasants, shepherds, children and women of that rural environment. The sociological and little-known Hudson is born there. He will always carry the pampa in his heart and this is how he tells it in a letter to his brother Alberto, when he invites him to return to study the birds of Córdoba, where he was installed. It was already late: “I thank you, but I won't be able to, sometimes I think that of the two paths I took in life, I chose the one that was least convenient for me. I will never forget the pampa”. Explicitly or implicitly, Argentina is present in the twenty-four titles that make up his work.

Hudson is Argentine despite having written in English, because of his work, because of his feeling of nostalgia, because perhaps like no other writer, he reflected the virgin pampas plain of barbed wire and foreigners. He is also an English-speaking gaucho, and that spirit embodies him in English literature of the early twentieth century. Hudson allows us to trace a wide path towards literature, and for those of us who consider ourselves bibliophiles today, he also encourages us to enter the world of the old book.

In 1923, a year after his death, J M Dent & Sons Ltd. published the complete bibliography of twenty-four works, in print runs of 5,000 for England and 3,000 for the United States. Currently only sixteen of his twenty-four books have been translated into Spanish in various editions of quality and format.

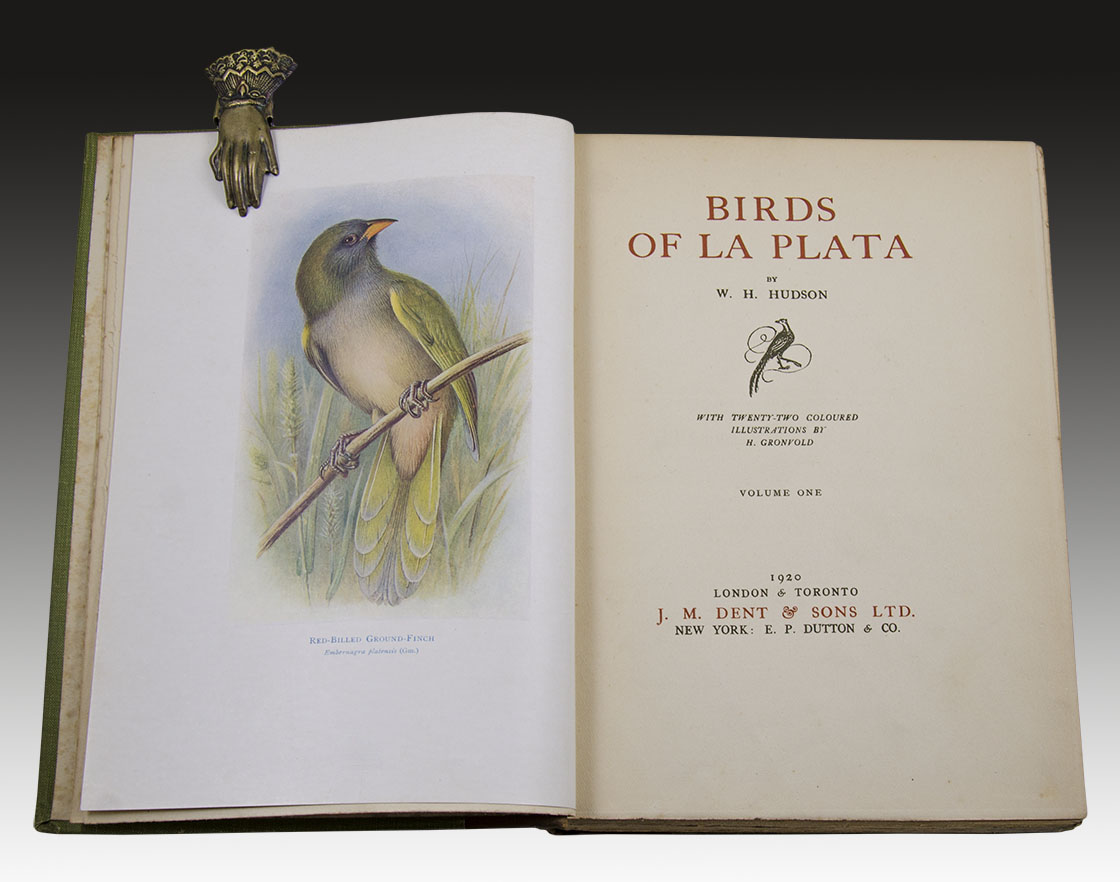

As a bibliographical value, without a doubt, Argentine ornithology in its first edition of 1888-1889, is the most valuable. Of this work, in two numbered and signed volumes, including 22 color plates; only 200 copies were published. 434 species were treated. The edition that Hudson released alone in 1920, now without the collaboration of Philip Lutley Sclater, is more frequent on the market: Birds of La Plata.

The Purple Land is his first unsuccessful novel from 1885. Only in the second edition of 1904 where Hudson shortens the name of The Purple Land that England Lost, to simply "The Purple Land", the work and the author acquire a certain prestige in the competitive literary market of London. In Argentina we find several finely illustrated prints, particularly that of Guillermo Kraft from 1956, with drawings by Enrique Castells Capurro is one of the most interesting. The work, as we have already said, is criticized by Jorge Luis Borges and, together with El ombú and Far away and a long time ago, allows Hudson to be introduced to gaucho literature.

In a Spanish edition of 1927 we find an epilogue by Miguel de Unamuno who in a paragraph expresses: “Superb work! I don't know another, in Spanish, that has given me better what I feel like calling the soul of Uruguay. The book reminds me in places of Borrow's The Bible in Spain, but how profoundly it all makes sense! The author began, it is known, with the unmotivated disdain of the English -over civilized- to the natural, feeling on his shoulders the weight of a kingdom in which the sun does not set, without any desire to make himself pleasant, but deep life won him of the eastern gaucho. He says that he is not a landscaper, but throughout his story he encourages, without descriptions, the landscape that makes up the oriental landscape, interior landscape: as in Cervantes. Well, on the other hand, he does not leave the book to remember Don Quixote; it is quixotic. Conversation Bee calls himself the author and gives us a honeycomb of the tastiest wildflower honey. Honey! He himself once says of something that it is not love but a sacred species of affection that resembles love.”

The other extraordinary element of the Hudsonian language is the property of the gaucho translated into English. He makes his beings speak in the barbaric, symbolic and expressive way that corresponds to the circumstance. Thus, in very pure English, the gaucho periphrasis appears as charged with humor and advice as in its original language; and in spontaneous expression, mischievous intent, grace, picturesqueness, and smugness come together with the amorous metaphor and chivalrous twist of the gaucho manner. Cunninghame Graham, his friend, has pointed out in the prologue to the first edition of The Purple Land a rosary of gaucho sayings and idioms of original grace. In 1996 Zurbarán editions takes the paintings that Florencio Molina Campos had done in homage to Hudson's work and produces an edition that combines art and literature with the same expressive quality of everything gaucho.

Hudson portrait. The camera captured his bonhomie.

In 1902 El ombú and other stories was published, a very rare approach for the English world since the very particular language of gaucho culture is not understood in that area. The Spanish version also receives criticism since Eduardo Hillman, the translator, is more of a papist than the pope, giving the translation a forced gaucho tone, far removed from the original version. It is strongly criticized by Eduardo Espinosa (Samuel Glusberg) who well understands the spirit of the naturalist and sees in that transcription a betrayal of his style and intentions. Even so, El ombú... spread throughout the country, when authors such as Roberto J. Payró highlighted it as a classic of gaucho literature. New translations improve it and once again the 1953 Kraft edition, illustrated by Alfredo Guido, is one of the most recommendable.

Green Mansions was published in 1904 and was a success, both critically and financially. In 1959 the director Mel Ferrer took it to the Hollywood cinema, with the leading role of his wife Audrey Hepburn and a young Antony Perkins, still far from Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho; the film was a moderate success with the public. Read on its own after more than a hundred years, this story of a unique female being who lives in harmony with animals - she eats no meat, sings like a bird and weaves her garments out of spider silk - seems very peculiar and current in terms of environmental criticism.

Margaret Atwood, the famous Canadian author of "The Handmaid's Tale", a fervent admirer of Hudson, since as he has the dual status of writer and compulsive bird watcher, tells us: "Green Mansions is a harbinger of things to come: Some features of this world would fit nicely, for example, in a treatise on veganism, or in James Cameron's Avatar movie, with its exotic giant flora, the female goddess tree, and blue-hued nature people and ears of goblin, not to mention many other science fiction and fantasy novels written since Hudson's time. But placed in its own context, Green Mansions becomes less cryptic. It is part of the huge explosion of fantasy and adventure literature that hit the reading world in the last third of the Victorian era and lasted until the first years of the 20th century. This period was the melting pot of 20th and 21st century science fiction and fantasy, which were not yet known by these names. Hudson subtitles his book "A Romance of the Tropical Forest," using "romance" as it was then generally understood, not an offspring of Pride and Prejudice, but a more fairy-like form, in which strict realism was not required. And, despite the joy of late Victorian utopias like William Morris's News from Nowhere, progress might not be inevitable and evolution might not be a one-way street, always leading to higher forms of life. What if it were the other way around, as posited in Charles Kingsley's 1862 children's fantasy The Water Babies, which contains an ape-reversion fable, and later, more seriously, in The Time Machine, in the that humanity degenerates into tenuous and ineffective childlike beings? Who are the prey of the carnivorous descendants of the working class? Previous certainties had been thrown into the blender and the results were truly worrying.”

“This is, then -we continue with the voice of Margaret Atwood-, the context of Green Mansions. It is a romance in a well-understood tradition; it is an adventure story set in an exotic setting; touches on one of the obsessions of his time, "the woman question," and presents a female creature of almost angelic purity; and calls into question the nature of human nature.”

Hudson had pointed to the same set of motifs earlier, in his 1887 utopia, A Crystal Age. Propelled into the future, the hero of this novella finds himself in a society that lives in beautiful natural surroundings, happily doing arts and crafts in the style of William Morris, and must deal with the environmental problems of the industrial revolution.

Although Hudson did not have a profuse social life, since his poverty and health conditions prevented him from doing so, he frequented some lunches and gatherings with prominent personalities of English literature. Among them, his closest friends were the writers Edward Garnett, Morley Roberts, and the eccentric adventurer Robert Cunninghame Graham, who prefaced his two books, Far Away and Long Ago and The Purple Land. Although they were not intimate, they had a mutual respect for Joseph Conrad, the Polish author who, like Hudson, had had to "adapt" the English language to his own style, with classic works such as Lord Jim or Heart of Darkness. Upon learning of the naturalist's death, Conrad said: Hudson was a force of nature, he wrote like grass grows.

The ruralist and environmentalist writer H. J. Massingham, a friend and admirer of Hudson, wrote presciently: "But though I doubt he has many more readers now than he did thirty years ago, the truth is that his name is imperishable and that his work has contributed to achieving an essence, a spirit and a vision complete in itself and without parallel in our literature". Two works by Hudson deserve special mention in the contribution to the knowledge of the British idiosyncrasy, On Foot in England (1909) and A Seller of Trifles (1921), in them is where we can also glimpse the sociologist Hudson, whose facet is the least known and studied.

Far away and a long time ago. The first edition of it in English.

Due to an illness that keeps him in bed for several months, he writes Far away and a long time ago -published in 1918-, using as input the vivid memories of his childhood in Chascomús and in the house of the Twenty-five Ombúes. The phrase that gives title to the book and the work itself will be very popular in Argentina, since since 1938 when Fernando Pozzo made the translation for the Municipality of Quilmes, the multiple and careful editions of Editorial Peuser are used as a school text until the middle of the 1970s, where it stops being read. However, the rural theme, the melancholic tone of the story and an almost iconographic view of the Rosista period in the Buenos Aires countryside make this his book -perhaps more mentioned than read?- In our midst.

In Argentina, following in the footsteps of Hudson also leads us to meet, read and enjoy various authors. Luis Franco, Ezequiel Martínez Estrada, Horacio Quiroga, the aforementioned Borges himself, and more recently Ricardo Piglia, Horacio González or Juan Sasturain.

Number 1 of the Trapalanda magazine, a Buenos Aires collective, comes out in October 1932. This new editorial proposal by Samuel Glusberg or (Eduardo Espinoza in his writer's pseudonym), came from closing the first stage of the Babel magazine, and had the collaboration of Luis Franco and Martínez Estrada, young friends of the brotherhood that formed under the wing of Lugones. That first issue was partially dedicated to the figure of Hudson, also with articles by Roberto Cunningham Graham and Espinosa himself. Contains a beautiful illustration of a cardinal, the work of Héctor Basaldúa.

In 1928 Horacio Quiroga published his first article on Hudson, simply titled "The purple land", we can consult it in The truck of the perfect storyteller. In 1929 he would publish the second, "On Hudson's 'El Ombú'", where he also values the social tone of the story, but criticizes Hillman's "creole" translation of "El Ombú", coinciding with Espinosa.

Luis Franco wrote about Hudson a series of articles in La Prensa (more than six throughout the years 1957 and 1976) and in 1956 he published Hudson on horseback. It is not a biography, rather it is a tribute with a personal interpretation where the poet from the mountains of Belén pays homage to the gaucho of the plain. In the year 202O, the publishing house Leviatán reissues Franco telling Hudson, but with the valuable addition of the prologue by the sociologist and essayist Horacio González, where he demonstrates his Hudsonian spirit and his knowledge of the subject already expressed in the book Remains of the Pampas, science essay and politics in the culture of the 20th century.

"Luis Franco clearly perceives in Hudson the experiential, sensitive streak, the rural happiness, the fabulous continuity between men and animals, the preference for life in nature rather than for the atrocious character of history," says Horacio González.

In 1951 through the Fondo de Cultura Económica de México, one of Hudson's lovers gave us what we consider to be the most heartfelt biography, we refer to Ezequiel Martínez Estrada who published The Wonderful World of Guillermo Enrique Hudson. The author of Radiography of the Pampa and The Head of Goliath, shows a profound knowledge of the honoree, not only of his work, but of his spirit and his feeling for nature.

He contrasts the work of Martínez Estrada with the ascetic, punctilious and almost surgical work carried out by Alicia Jurado, after her research trip to London. In 1971 the National Endowment for the Arts published his Life and Work of W. H. Hudson. Perhaps we owe the most popular biography of the naturalist to the man who had the privilege of writing, together with Borges, the essay What is Buddhism?, but we believe that the critical and distant gaze of A. Jurado does not fairly reflect the life of the naturalist of the lost pampas.

Between Estrada and Jurado, it is true what the author of the Loser's Manual, the current director of the National Library, states. There, Juan Sasturain maintains that "Hudson is an unavoidable writer for us, beyond false chauvinisms «if he is ours» or «theirs»: -it is obvious that he belongs to English literature- his unique perspective and experiences and extremely rich personal testimony that has left in luminous texts about an era and certain environments of our country make it essential reading”.

He also deserves to be included in the group of "Hudsonians" Ricardo Piglia who, in El viaje de ida, makes the protagonist travel to England to teach classes on W. H. Hudson, starting the plot of the novel. In his posthumous work The Diaries of Emilio Renzi (which I fervently recommend) Piglia explains: “The writer, naturalist and ornithologist W. H. Hudson, on whom Renzi teaches his class at the university, faithfully represents the ambivalence of someone who feels rooted in a culture and lives in a different one: “I was interested in writers tied to a double belonging, linked to two languages and two traditions. Hudson fully embodied this issue” (p. 36). The perspective with which the environment is observed is rooted, both for Hudson and Renzi, in their memories of Argentina, the experiences lived during the dictatorship and, mainly, the language: “English made me uneasy, because I make mistakes more often than not. of what I would like and I attribute to these misunderstandings the threatening meaning that words sometimes have for me” (p. 22).

As we can see, Hudson opens up a broad panorama of Argentine literature, art, and natural history; of the gauchesca and English sociology, all situations that do nothing but make our lives happy. In his birthplace, today a provincial historical museum, in one of the panels where we present his works, we dare to make a suggestion to the visitor: "Don't die without reading Hudson." And it is that we simply transfer Borges's opinion about La Tierra Purpurea to all of his work. We know that, like those beautiful things in life, Hudson can bring true happiness to whoever looks at it.

* I want to thank Roberto Vega for the invitation to write this article for Hilario's undertaking, which selflessly contributes to Argentine culture. To Eve Lencina and Enrique Pedrotti for the deep and permanent literary study they carry out of the work of Guillermo Enrique Hudson.