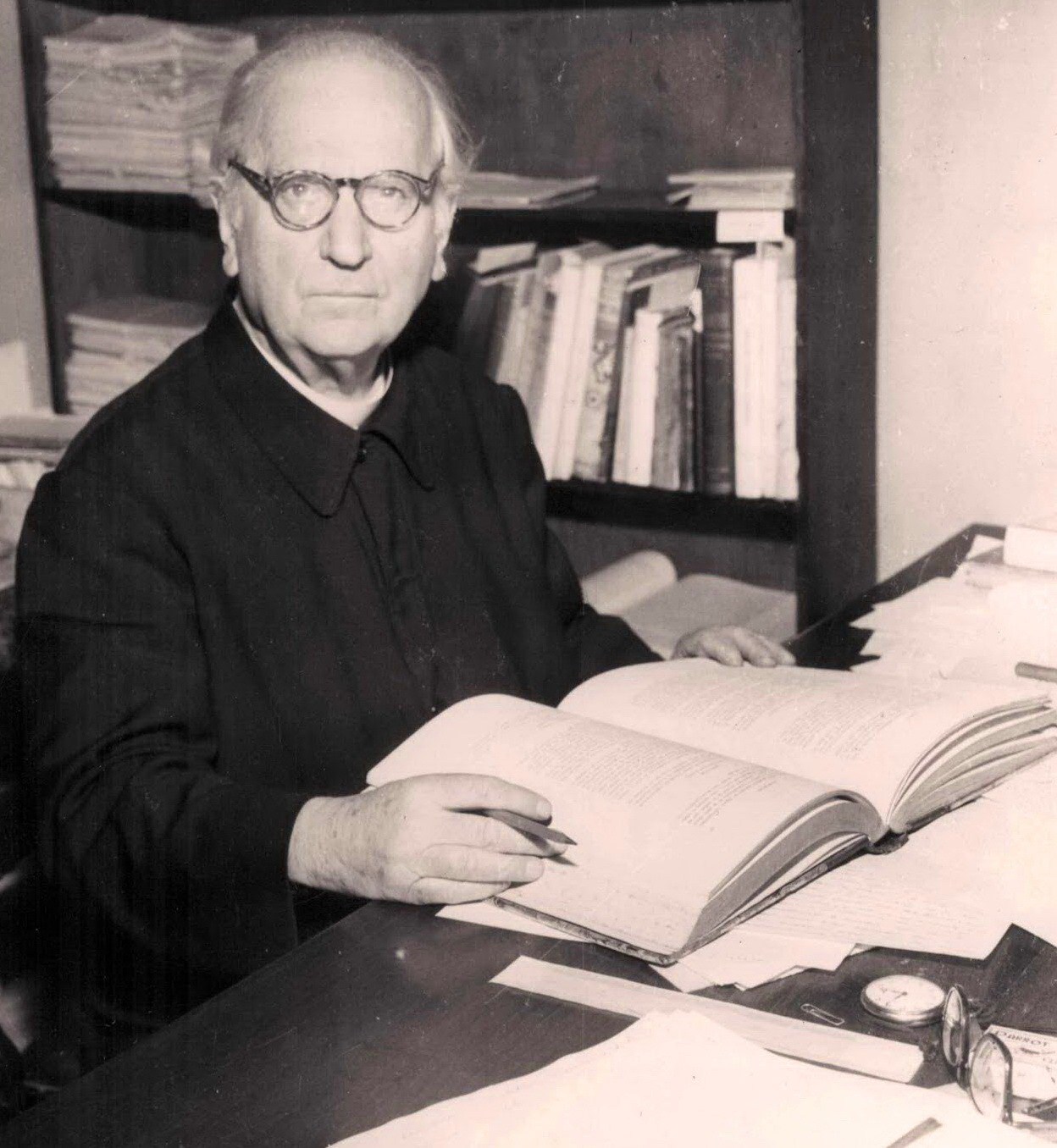

After the death of Guillermo Furlong, which occurred in the city of Buenos Aires on May 30, 1974, some bibliographies were made to publicize the different topics on which he published and facilitate their location when they were published in newspapers, magazines. dissemination and academic and university publications.

The Central Library of the Universidad del Salvador included a brief enumeration of these, in the eleventh installment of its Boletín (Bulletin) (1984).

In volume 43 of the Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu (Rome), published in 1974, between pages 485 and 511, the Jesuit historian Hugo Storni offered another bibliography, limited to Furlong's works referring to the activities of the Society of Jesus between the years 1585 and 1768, the specific ones, the cultural ones, their organization, the representative figures and some related topics.

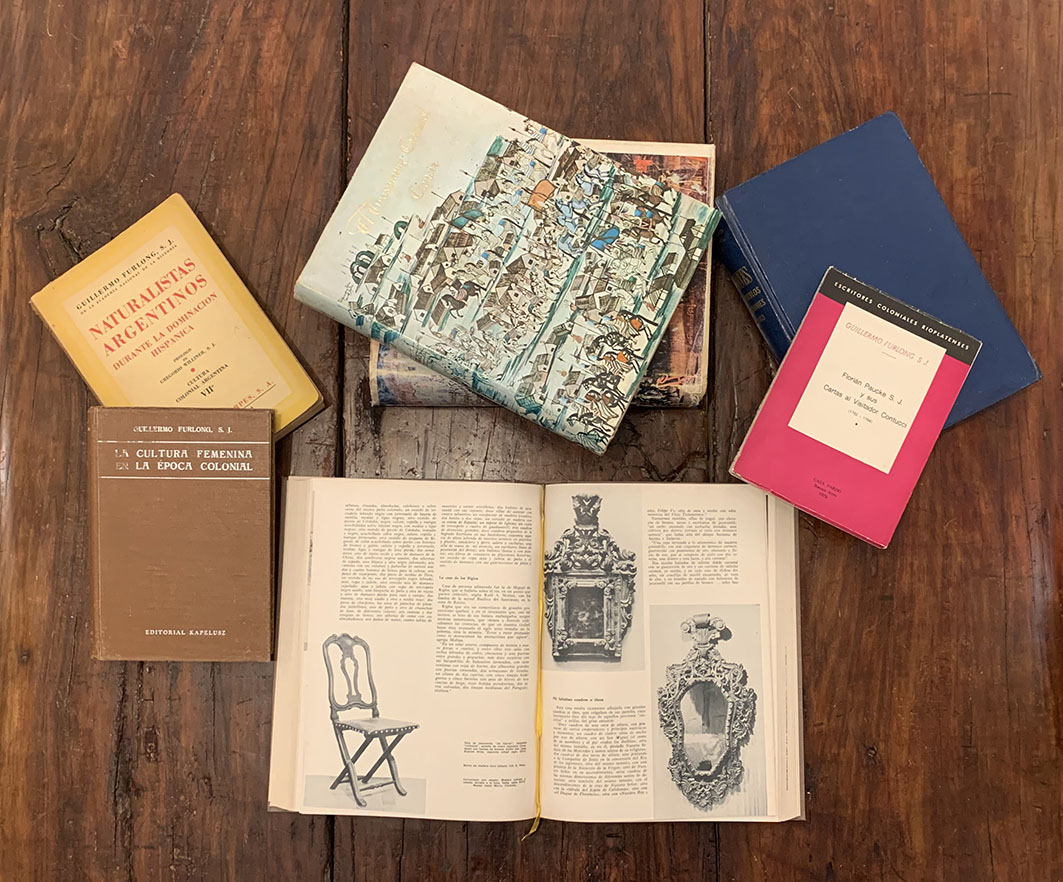

In the month of December 1994, the National Institute of Historical Research Juan Manuel de Rosas, in its Federal Star Collection, published my book The Hidden Work of Father Furlong, with a prologue by Fermín Chávez, where I brought together his 389 works signed with different pseudonyms.But in none of the cited bibliographies is there more than a tangential reference to the many works of this priest that remained unpublished for various reasons and those left by him at the time of his death.During Furlong's lifetime, the first edition of the bibliography made by Geoghegan appeared, in which he collected the production up to the year 1957, with an introduction by his brother José Torre Revello.When Geoghegan took on the task of updating the work -that is, adding the last 17 years of uninterrupted activity, and adding those omissions that the bibliographer himself had pointed out- this updating work allowed him to incorporate a section that he called The unpublished writings. To achieve this, he relied on the Jesuits Ismael Quiles and Ernesto Dann Obregón, thanks to whom he had access to the priest's archive at the Colegio del Salvador.This second edition, corrected and expanded with the publications of his last years, and with unpublished works, was published in the Bulletin of the National Academy of History (Buenos Aires) in volume XLVIII published in 1975.In this section I have counted 312 entries with the description of each work, grouped under the headings: General Works 9, Argentine History 83, Geography, Cartography and Vespucci 11, Education 17, Literature 14, Bibliography and Printing 9, Libraries and Library Science 4, History of Medicine 4, Ecclesiastical History 25, Society of Jesus 14, Theology and Philosophy 20, Asceticism and Mysticism 2, The Holy Gospels 1, Hagiography 1, Dictionary 1, Biographical works 25, Jesuits 28, Miscellaneous topics 27, and Bibliographic reviews 17.

The detailed analysis of each entry and its comparison with those referring to the books, pamphlets and articles published by Furlong, show that not all those included as unpublished really are. Furlong did not keep copies of his published works, but he did keep his manuscripts and typed texts in folders and boxes -in which he added everything of interest to him-; these were listed among the unpublished writings, when in fact they were not.

I treated Furlong for many years, which for me were few. During his lifetime I was able to consult in his cell some of his archives in which I found published works, the complete manuscript and the drafts of others; typed texts with translations from English, Latin and Greek; unfinished bibliographies; newspaper and magazine clippings; negative and few positive photocopies; works with corrections and additions; ballots with regestas (1), others with loose annotations or transcriptions of documents; files with bibliographic and typographic data; pedigree charts; lists of people and chronologies of events.

Retrospective American Cartography; South America and especially the Río de la Plata, 1500-1880, is a corpus of approximately 682 maps with essential descriptive data, a historical-geographical analysis and citations of similar important repertoires that have dealt with the same maps. . The documentary material of this work was consulted and photographed from 1938 by Furlong in archives in the United States, Europe and our country.

The article Manuel Belgrano, published in volume 19 of the magazine Estudios (Buenos Aires) in 1920, although signed by R.P. Vicente Gambón S. J., this article was written by Father Furlong.

In 1975 Geoghegan reported in his bibliography: 32 years ago he had been in possession of a gentleman residing in Buenos Aires, the Manual of Argentine history; text for high school, 250 pages.

Notes:

1. Editor's Note: Lists.

2. This word comes from the Greek, and means "different name". According to José Martínez de Sousa in his “Dictionary of typography and the book” (1974), it is the name of a person who is not the true author of a work, but who appears in it as such.