With various woods such as cardón and maguey for the northwest, others harder for the northeast, or higuerón, the wood of fruit trees such as orange, lemon or sour cherry for Mendoza, the imaginers of various provinces of Argentina have expressed their abilities and wisdom.

Since the seventeenth century and as a result of the Council of Trent, which favored that images were not only an object of pure delight, but also a formidable propaganda instrument aimed at attracting the people, the evangelizers of America sponsored the holding of saints in homes to that these images become part of daily life and serve as protection for people, their livestock and belongings. These images, many times described in the 18th century as "indecent" by the Church's leadership, were criticized "(...) for the scientific ignorance of art (...)" or directly burned, considering them unworthy. Around 1800, when Benito Arias took over the curate of Casabindo -Jujuy- he had six sculptures burned due to "the sum of imperfections with which they had been painted”.

However, those people who manufactured saints, virgins and Christs for private devotion, continued working to meet the needs of their communities that appreciated those works that were and are, in many cases, considered primitive, naive and even ugly, crude, bad made, vulgar and unspiritual.

This long adjective for some time has been put into discussion and that popular imagery found great defenders in the 20th century thanks to researchers and specialists who have gone in search of an original, unique and identity art or craft.

These imaginers, with precarious tools and sometimes also, with limited knowledge of the sacred books and / or the lives of the saints, achieved pieces of great value that are becoming known and generate new interested parties, tasters and collectors.

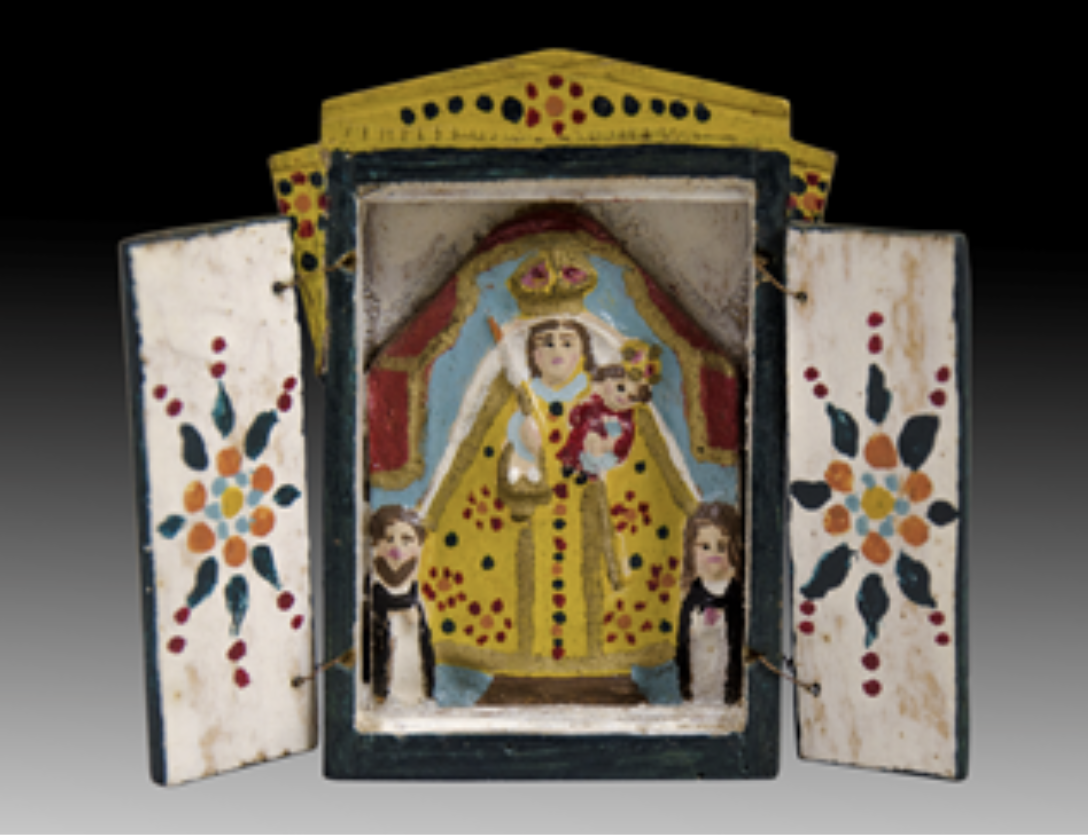

It is known from period documents that in 1702 there was a "maker of altarpieces" in Cochinoca (Puna Jujuy). The information does not specify if they were church altarpieces, very normal for the time that there was a carpenter for this purpose, or were the portable altarpieces that were kept in the houses with the favorite saints (accompanied by the various animals of which they were protectores), for family devotion as described in 1935 by Alfonso Carrizo referring to those homes in the northwest by indicating that "the most important part, the soul of the house, is an open niche where the saint or virgin is”.

We know imaginative artisans who developed their activity from the northwest to Cuyo and the northeast, in the 19th and 20th centuries, such as Ruperto de la Vega from La Rioja; Esteban (alias San Pedro) from Salta, Andrés Arancibia, also from Salta; Salomé Guzmán in Tucumán; Justina Cárdenas, Nicéfora Díaz, Juana and Catalina Segura and José Pérez, in Mendoza and Alberto Rolando Gauna, from Corrientes.

Andrés Arancibia, who was born in Belén (Catamarca) in 1890, arrived in Salta in 1906 where he developed his profession as a santero. For the carvings of him he used poplar or willow wood, and the faces or heads of the images of him were cast with plaster in a mold, this is a technical solution widely used in America since the colony. The same did Hermógenes Cayo (1905-1969, who defined himself in the electoral roll of 1947 as a "painter") in the Puna of Jujuy for the making of his images. He used cardón wood that he roughened with a rasp (wood file) and other rustic tools. In Jorge Prelorán's film (Hermógenes Cayo, 1969) he is seen working with that tool on the body of a virgin to generate the folds of the tunic that covers her back and crosses in front of her body. Her face, as we said, is cast and cast in plaster; her hands, the crescent, the feet peeking out from under the robe, and the base of it are made of harder wood, perhaps cedar. The arms of the crucified Christs are made with this wood, as seen in the aforementioned film.

Before polychroming the images (Arancibia with oils, Hermógenes Cayo with industrial paint) these artisans covered the imperfections of the wood with chalk and glue.

The Hermogenes pieces have more grace and a better finish than those of Arancibia. Hermogenes, in addition to making the large urns that used to go out in procession at the festivities of Casabindo and Cochinoca, made small travel urns that were carried by people in their clothes or in their luggage. One of these tiny urns was recently finished in Hilario.

The most common production of the image makers of Mendoza was the realization of sizes that measured between 10 and 30 cm. in fig, orange or lemon woods. There are several private collections in the province with these works. In addition, they made others of approximately 5 cm high that were used by the ladies who carried them in their bags and the soldiers in their backpacks.

These santeras and santeros from Mendoza, previously named, generated a style for their larger creations with the following characteristics:

- pyramidal design,

- hieratic and frontal,

- shallow depth,

- complete carving of the image and its attributes (flowers, palms, etc.) or the Christ Child in the case of the virgins or Saint Anthony,

- rigid and non-flared clothing cloths,

- straight, smooth back, only with incisions indicating the folds of the garments.

The tools they used were also few and rustic. The small details of these images were made with knives and glass fragments taken from broken bottles.

Going northeast, we find another quality imager like Ramón Cabrera, from the capital city of Corrientes. He also made pieces that do not exceed 7 cm and are carved with excellence such as Santa Catalina de Alejandría, Virgen de Itatí, Santa Librada, San La Muerte (Saint Death) and Pombero, among others. San la Muerte occupies an important place within the profane saints. He is represented as sitting and holding his head with one or both hands, the elbows resting on the knees. When he appears standing he carries the scythe that he holds with his right hand. He is a protector of bad marriages, "advocate" in matters of gambling, infallible to recover lost property and to cause harm to or to counter someone. They are made of wood, lead from bullets and human bones. The Pombero is the most popular of the Corrientes goblins. He is short and stocky and always appears with his big straw hat. He has hairy feet and is a heavy smoker. He is a faithful friend who can be trusted in any time of need. Santa Librada is a female version of the crucified Christ. According to legend, to escape the attractions of her beauty as well as the suitor her father had assigned to her, she prayed to God to grow a beard. Her father, then, had her crucified. She is required by escapees from justice who escape from the police who are looking for them. She recites the following, for her protection; "Santa Librada / get me well / out of this shot”.

In the book National Artistic Heritage, Province of Corrientes (1), edited by the National Academy of Fine Arts, we have recorded in the introduction the existence of small images probably of Cabrera and on pages. 201/202 we incorporate a beautiful and graceful image of Saint Anthony of Padua who is sitting and reading, 11.5 cm. and of the twentieth century. In this book we also include fifteen pieces of the more than thirty that we inventoried of popular imagery, which were unknown until now because they were in the hands of individuals and a record of said material had not been made. They are, generally, carved in wood and polychrome. Some have Paraguayan influence and are characterized by concise language, devoid of excessive realistic data. There are several representations of the Crucified Christ accompanied by a kneeling angel, who collects the blood that flows from his side in a chalice. This attractive iconography has its antecedents in German engravings from the 15th century.

In Traslasierra, Córdoba, an imagery of quality, originality and easy identification by its construction method has been generated since the 19th century. They are semi-hard wood carvings, barely a few centimeters deep. The mantles and other pieces of the clothing are made of glued cloth, the faces of plaster and the attributes such as banners or the model of the church in the case of Santo Domingo de Guzmán are independent pieces, measuring 33 cm., Or the San Pedro Nolasco, 31.5 cm. There was a large production of these pieces that covers the almost complete saints.

In this quick tour of the popular imagery of our country we have been able to verify the existence of imageiners of value and creative capacity in both the 19th and 20th centuries. We are sure that we have forgotten some of them but those included here have marked a mark and an impossible path to avoid when it comes to valuing popular creativity.

Notes:

1. Adolfo Luis Ribera, Héctor H. Schenone, Iris Gori and Sergio Barbieri: National Artistic Heritage, Province of Corrientes. Buenos Aires. National Academy of Fine Arts. 1982.