Alfredo González Garaño (1886-1969) was a passionate, cultured and generous collector. Together with his brothers Celina and Alejo, he was part of a circle of artists, writers and cultural promoters who left an indelible mark on Argentine art and culture. The artistic genealogy of the González Garaño family had been anticipated in the portrait that, around 1860, the famous Italian artist Baltasar Verazzi had painted of his maternal grandmother, Cristina Castro Ramos Mejía.

Parera's group. From left to right, Alfredo González Garaño, Alberto Lagos, Alberto Girondo, Carlos Ayerza and Aníbal Nocetti. Gonzalez Garaño Legacy. National Academy of Fine Arts.

From his beginnings in art back in 1908 as a member of the "Parera group", together with Alberto Lagos, Carlos Ayerza, Aníbal Noceti, Ricardo Güiraldes, Adan Diehl, Tito Cittadini, Gregorio López Naguil, Alberto Girondo, Alejandro Bustillo, he fostered fruitful exchanges that would continue in Paris and then in Mallorca, under the teaching and friendship of the Catalan artist Hermenegildo Anglada Camarasa. Although they emerged from the bosom of the cattle aristocracy, almost all of them had the virtue of putting the benefits of their inheritances in the background to become artists or patrons. This circumstance allowed outlining new perspectives in the relationship between tradition and modernity. Testimony of these interests are, for example, the paintings and drawings that Alfredo González Garaño made throughout his life. On this occasion, I focus on three moments of his artistic activity that are closely related to his traveling practice since, as Jorge Monteleone [1] proposes, whenever there is a trip there is a story, whether textual or visual. Traveling brands that take the form of letters, postcards, photographs, notebooks or works of art and make up the plot of a memory that transcends chronologies.

His passion for travel, shared with his wife, María Teresa Ayerza, is a fact that marked the course of his life. These journeys constituted experiences of a cultural nature, but above all vital, both in Europe and in America. Thus, I point out those that occurred in the first decades of the 20th century and that I consider crucial, since they correspond to moments of intense discussion between modernizing projects intertwined with Americanist concerns. These journeys took place in the Argentina of the Centennial in which the International Art Exhibition housed among its foreign shipments the brilliant chromatic explosion of the canvases of Anglada Camarasa, one of the most admired artists in that crucial contest, already consecrated in Paris by the success sales and exhibitions. In that same year, A.G.G. travels to Paris where he joins the circle of disciples of the aforementioned Catalan artist. The following year, with his wife, they bought the oil painting Sevillana, c. 1911-12 [2], thus beginning a series of acquisitions that would later form part of the heritage of the National Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires. It is interesting to emphasize this couple as promoters of the master's work in Buenos Aires with a first individual exhibition at the Museum in 1916. This purchase was followed by others: Valenciana entre dos Luces, 1908 [3], Sibila, c. 1913 [4], Gypsy woman with child, c. 1910 [5], Portrait of Marieta Ayerza de González Garaño, c. 1924 [6].

I want to highlight a fact that begins in Paris. In the French capital, the couple attended the seasons of the Russian ballets managed by Sergei Diaguilev, seasons that would be repeated in Buenos Aires in 1913 and 1917 with the presence of Vlaslav Nijinsky. In this regard, in the materials of the "González Garaño Legacy" of the National Academy of Fine Arts, there are two revealing photographs. One, dedicated to “Marietta”, corresponds to Tamara Karsavina; the other, by Nijinsky, dedicated to Alfredo, both signed and dated in Buenos Aires in 1917. The two pieces show the friendly bond between these celebrated dancers and the González Garaño couple. This circumstance will have repercussions in an interesting indigenous ballet project that A. González Garaño and Ricardo Güiraldes will title as Caaporá. [7] The idea began to materialize in 1915 under the influence of the Russian ballets.

Given the exploration of Russian popular legends, both friends find an interesting option to specify an aesthetic program that will activate American myths and legends, also integrating music, literature, painting and dance within the framework of a transdisciplinarity that will add to the renovations of the moment. The purpose explored the Guaraní legend of the Urutaú that they learned through the stories of the anthropologist Juan B. Ambrosetti, then director of the Ethnographic Museum of Buenos Aires. While R. Güiraldes writes the stage text, the paintings of the costumes, sets and decorative pieces of the staging are shared between the two friends. And although the first musical notations had been entrusted to Pascual De Rogatis, in those Buenos Aires meetings of 1917 it was Stravinsky the musician whom Nijinsky and González Garaño thought of for the musical structure of the ballet. Nijinsky reserved for himself the role of principal dancer as well as choreographer. The story is simple: a Guarani cacique decides to give away his daughter in marriage for which he organizes a competition that would define the best among peers. When a warrior from the enemy tribe is victorious, the cacique summons Caaporá, an evil deity, who breathes a curse on the princess. The people demand the healer of the tribe to cure the princess, but contrary to expectations, he announces the false death of the suitor; The young woman, overcome with pain, metamorphoses into Urutaú, a mythical bird whose cry gives rise to "the eternal lament of the Guaraní jungle", a legendary explanation of the origin of the Iguazú falls. This ballet, never materialized, is key to the idea of turning the teleological paradigm of the modern project upside down: it was not so much about looking to the future, but about focusing on the past of an ancestral mythical imaginary with a new perspective. The very idea of transdisciplinarity was already a “modern gesture”.

Scenography for the Ballet Caaporá. A. González Garaño and R. Güiraldes. Museum R. Güiraldes of San Antonio de Areco.

From this initiative the paintings of the sets, costumes of characters and decorative elements are preserved. All this material corresponds to the collection of the Creole Park and Museum of Gauchesque Affairs “R. Güiraldes” of San Antonio de Areco. In the paintings, the influence of the intense decorative sense expressed in the sinuous forms is noticeable, as well as the strident palette that we recognize in important artists who, such as Natalia Goncharova or Léon Baskst, collaborated with the ballets; also of the paintings of Anglada Camarasa who then represented the connection with the modernisms that unfolded in variants at times symbolist, at times expressionist. Both in one or another option, painting moved away from the descriptive and literary realism of the academy to delve into areas of greater pictorial renewal.

In addition, in the aforementioned "Legacy", revealing photos and postcards referring to the numerous trips made by the González Garaño stand out. Thus, a photograph by Guido Boggiani that shows a woman from the caduveo group of the Chaco region. On this subject, Boggiani's ethnographic studies will later constitute an input for the works of Claude Lévi-Strauss. These photographs were marketed by the printer Rosauer, who had his business on Rivadavia Street, data that appears on the back of said photograph. If to this data we add a portrait of "Marietta" by the Uruguayan artist P. Blanes Viale" (Iguazú, May 1916), we deduce that the couple would have traveled to the Chaco region where they would have known these legendary stories. Caaporá will express a strong commitment in favor of the local, assuming the risks involved in re-semanticizing a Guarani myth with a language filtered by the experience of the avant-garde. But this is not an isolated event in the context of Buenos Aires in the 1920s. In fact, the newspaper Martín Fierro repeatedly introduces pre-Columbian motifs and even reproduces images of this unusual ballet, which shows that Americanism is already at the center of the disruptive debates. These proposals focus on the visualization of a regional model separated from the academic repertoires of the centenary, and in solidarity with the innovative ideology of the time.

Secondly, we consider another trip: the one carried out through American territory, initiated at the end of '16 by R. Güiraldes with his wife, together with María Teresa Ayerza and A. González Garaño who from the Retiro station march to Mendoza, there they will take the transandino that will take them to Valparaíso and, bordering the Pacific coast, they will arrive at the island of Jamaica. This trip will be known for the novel Xaimaca that R. Güiraldes edits in 1923. Of this new journey, parallel to Güiraldes' annotations for his novel, the visual records of the American environment that are verified in a notebook entitled "Journey to Jamaica . 1917”, whose authorship corresponds to the aforementioned travelers. Along with these records, we have a new set of postcards that G. G. gathered during the journey and that are part of the aforementioned "Legacy". If, as in Caaporá, the ritual and symbolic component is central, the same does not happen with the trip to Jamaica. This second experience advances on the observation and interpretation of the cultural, social and natural environment, where travelers leave traces around the problem of colonialism, pre-Hispanic populations and the black component present in Panama and Jamaica.

These materials will make up a corpus created in the context of the River Plate modernities of the last century that leads us to broaden Americanist worldviews from specific ways in which the world of the natural pre-modern is interpreted, while certain forms of the ritual and the symbolic. It is a travel story, that is to say, a diary, whose name derives from the Xaimaca voice that in the local language -Taina- means "the land of blessed water". In this notebook they write down data referring to stay and transfer expenses and draw caricatures of characters with whom they share the adventure, integrating them with cultural exchanges, which anticipates later practices that on the island of Mallorca reiterated as a kind of what the surrealists will call “exquisite corpses”. This notebook reveals the "travel marks" of a journey made without prior organization. The trip will extend to the Caribbean Sea, outside the usual course of Eurocentrism typical of the intellectual and wealthy class to which these young people belonged, to explore the new possibilities that the American territory offered them. Keys to this disposition are the indications of the popular environment: markets, fruit vendors, hat makers in Paita or indigenous types in Peru. And just as it happened in the case of Caaporá, together with the notebook, we have other postcards acquired by G. G., gathered under the description “Souvenir Folder of Native Life. Republic of Panama”, or “Souvenir of Colon and Cristobal” and “Souvenir of Hotel Washington. Colon Panama”, whose most recurrent images are representations of blackness, colonialism and, to a greater degree, of nature.

Exquisite corpse, signed by H. Anglada, R. Güiraldes, S. M. Anglada and G. López Naguil. Former A. González Garaño collection. SEE MORE

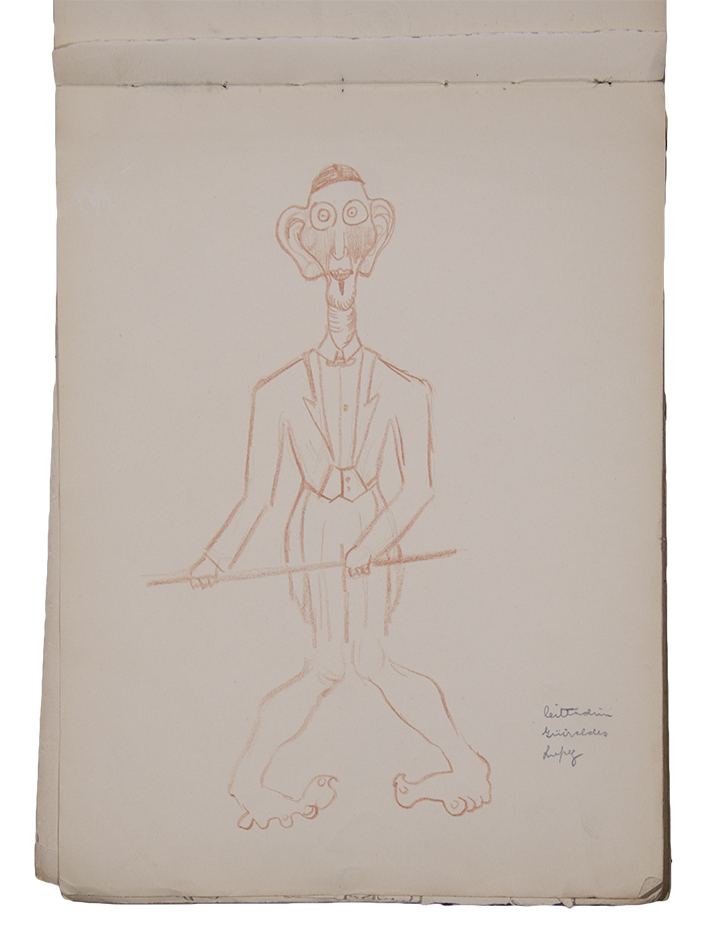

The third aspect is linked to the installation of Anglada Camarasa in Puerto Pollensa, Mallorca, due to the outbreak of the Great War. This fact also prompted the transfer of his Latin American disciples, among them, R. Montenegro, A. González Garaño, R. Güiraldes, A. Lagos, G. Leguizamón Pondal, A. Nocetti, T. Cittadini, R. Ramaugé, G. López Naguil, R. Franco, and A. Diehl. Regarding the interaction of these young people, the archives consulted allowed me to notice photographs referring to the days of enjoyment at sea, picnics in the open air, walks through pine forests or mountains, which reveal the relaxed atmosphere that was lived in that Mediterranean coexistence. They are representations in accordance with the dominant myth of Mallorca imagined as "island of calm", "arcadia desired by travellers" and give shape to a microcosm where the individual dissolves in the indolence of that landscape. Like his friends, González Garaño paints landscapes that, from 1922, he will send to the national salons of Buenos Aires trying to conquer the artistic esteem of critics and the public that, finally, did not materialize. This coexistence was also conducive to portraying each other with his companions, in a serious or parodic key, in pieces that testify to the interest in playful experimentation together with the climate of complicity that they lived. In line with this predisposition to enjoyment, some drawings of shared authorship are equally interesting, along with other drawings and paintings in which certain gestures typical of the avant-garde can be pointed out that have to do with experimentation on the image, what the surrealists would call years then "exquisite corpses." Just as it had happened years before with the travel notebook to Jamaica, this time the same thing happens with G. López Naguil, R. Güiraldes, A. González Garaño, S. Martini, then wife of Anglada Camarasa, T. Cittadini and with Anglada himself. It is a visual device where the caricature appears as an ideal resource to break the canon of pictorial tradition and find a new image of the surrounding world in humor.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Crafts

Notes:

1. Monteleone, Jorge (1999). The travel story. From Sarmiento to Umberto Eco, Buenos Aires, El Ateneo.

2. National Museum of Fine Arts of Buenos Aires.

3. National Museum of Fine Arts of Buenos Aires.

4. Anglada Camarasa Collection of the La Caixa Foundation in Palma de Mallorca.

5. National Museum of Fine Arts of Buenos Aires.

6. National Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires

7. In this regard, see: Babino, María Elena. (2010) critical study, Ricardo Güiraldes and Alfredo González Garaño. Caapora. An indigenous ballet in modernity, Buenos Aires, Van Riel Gallery.